I Like Writing Code

On finding joy in slow, imperfect code in an age of copilots, agents, and chatbots. 1.2k words, 5 min reading time.

On Thursday, January 15th, 18:00 - 20:00 CET, I’ll be giving a 2-hour workshop on R package development in Positron. Details and registration here.

To prepare, I have been writing the code for the workshop from scratch, and I have made a very deliberate choice: no Copilot, no AI assistants, no autocomplete that finishes half the line for me. Just me and Positron, with Copilot Positron Assistant disabled.1

With some time off over the holidays I was recently able to spend ~6 hours heads-down in my IDE. I spent more time writing code that afternoon than I’ve been able to over the entire semester I’ve been here, combined.2

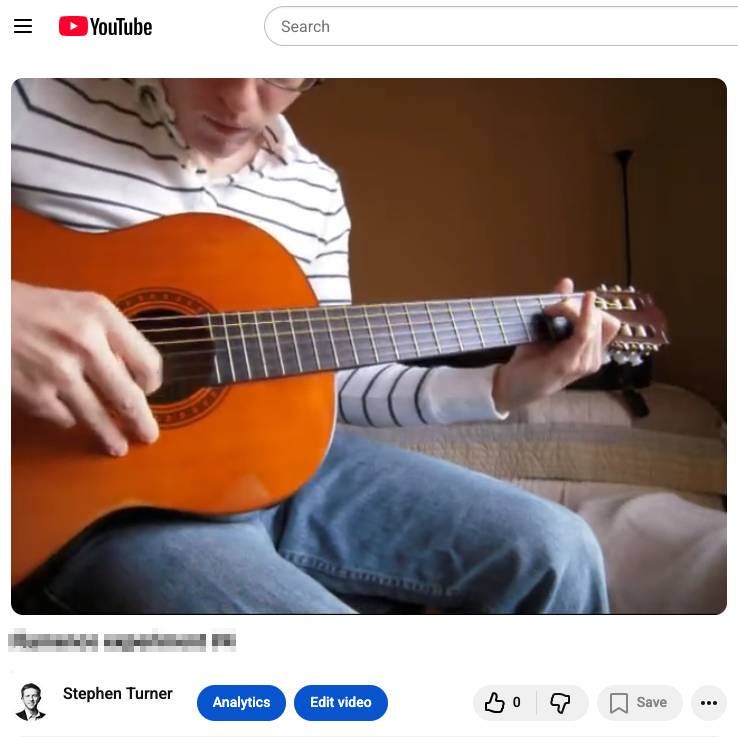

I lived in Nashville Tennessee for about 6 years, and as one does in Nashville, you pick up an instrument and find other musicians to pick around with. Although I left Nashville over 15 years ago, my house is still crowded with 4 guitars, 2 ukeleles, a banjo, a violin, a mandolin, two trumpets, a hand pan, harmonicas in every major key, and a piano. Writing code this way reminds me of how I feel when I sit down to play an instrument.3 I’ll never be able to produce any sound from any of these instruments that sounds as clean, polished, and technically perfect as what I can hear from any random track on Spotify. With GenAI music tools like Udio or Suno I can type a prompt and get an original track that in a purely technical sense will surpass anything I will ever play in my home office / studio.4 Yet I still enjoy pulling my Martin out of its case. I love the smell of the Mahogany. I enjoy the technical struggle through difficult fills between chord changes. I still enjoy getting a phrase just right, even if the recording quality in my head is better than what my hands can ever deliver.

Writing code without AI feels like that. I know, objectively, that I can write code faster and often better with a copilot watching over my shoulder. I can scaffold a package, generate boilerplate, and even nudge an LLM toward passable unit tests. But when I turn all that off, I got something back that I had not realized I was missing. I had to look up function documentation. I had to write better tests and examples. I get to rediscover little idioms in R that I used to reach for automatically. I feel that pleasant friction of having to look something up, read the documentation, and think for a moment about why the design of the function is the way it is.

Part of this might just be simple nostalgia. In my previous roles as a principal engineer (Colossal), a large part of my identity was tied up with writing code, reviewing others code, mentoring junior developers, and shaping the architecture of systems. There was a craft to it. You could see your influence in the codebase and in the people you worked with. That sort of feedback is immediate in a way that meetings and proposals rarely are. A mentoring conversation might echo months later. A grant proposal might take a year to read out as funded or not. A pull request closes this week.

Now, the things I am responsible for span strategy, people, budgets, and organizational priorities. Fun is not the relevant metric in that space. Outcomes, impact, and sustainability matter more. I understand that, and I take that responsibility seriously. It is important work, I’m good at it, and I love doing it.

Still, as I was building the examples and accompanying vignette materials for this R package workshop, there was a different kind of satisfaction. Designing a small, well scoped example function. Writing a compelling and motivating vignette. Thinking about how a future user will experience ?my_function the first time they type it, and how the examples in the documentation should tell a story. There is joy in that attention to detail. There is joy in chasing down a failing test and realizing you misunderstood a corner case.

AI tools change the texture of that experience. They are powerful, and I use them. They can help catch errors I might miss, suggest edge cases I would not have considered, and speed up generally mundane tasks, like writing unit tests with testthat. In a commercial or institutional context, all of that matters. For a production system, I want the best tools in the toolbox, and if that means augmenting my brain with an LLM that knows every CRAN package better than I ever will, that is fine.

But when everything is optimized for speed and correctness, something quieter gets squeezed out. The lingering decision over what to name a function. The hand tuned refactor of some complicated lapply() to a more elegant purrr::pmap() implementation that no one else will ever notice, but that makes the code read just a little more like a well written paragraph. The feeling that you and the code are in conversation, not that you are simply supervising a very smart autocomplete.

This is the tension I feel as I prepare for this workshop. On one hand, I want to show participants the most efficient, modern workflows, including how AI tools can make them more productive. On the other hand, I want to protect some small space where they get to feel the craft of it. Where they type out the function by hand, write the roxygen comments themselves, and watch devtools::check() fail for a concrete, understandable reason that they then fix. Not because this is a technically better approach, but because it can be fun, and that fun is part of what has always kept me interested and engaged when the work gets difficult. Being reduced to hitting the tab key repeatedly to copilot my way through takes these little joys away.

The end result will not be the most impressive repository on GitHub or package on CRAN. It might not even be the best version of that code I could produce if I let the machines help from the beginning. But the process matters to me. It is how I stay in touch with the part of myself that became a data scientist and engineer in the first place, before titles and calendars and committees.

On January 15th 2026, for two hours, I get to share that with a (virtual) room full of people, even if we also talk about modern tools and workflows. I am looking forward to it. Not because it will produce the most elegant and technically advanced R package for the public health applications, but because it gives me an excuse to sit down, turn off the copilots, and remember what it feels like to practice the craft I fell in love with years ago.

Coda: Andrew Heiss has a great section in the final lesson of his Data Visualization in R course, “Will R ever be fully replaced by AI?” (spoiler alert: probably not). I recommend reading it, especially if you’re an educator or a student.

Yes, the registration pages notes that the workshop will cover a few AI tools along the way. I’m limiting this to writing tests with testthat with a little help from Positron Assistant.

I love my new job. My calendar is full of meetings. I spent much of my time answering email, writing proposals, revising other peoples proposals, drafting papers, and helping my faculty strategize about theirs. It is meaningful, important, and I love it all. But it is not the kind of work that leaves my fingers tired from typing code or my brain pleasantly numb from spending three hours wrestling with some puzzling bug or optimization.

With apologies to musicians out there that reel in disgust at AI-generated “art” and music… A while back I had a problem with a racoon family coming into the house through the cat door at night. My kids named the intruder “Ricky.” I got Suno to write a twangy country song about Ricky’s adventures. It’s catchy, ngl.