AI-Enabled Biological Design and the Risks of Synthetic Biology

Chapter 3 of the National Academies report on AIxBio: Biosecurity implications for what AI can and can't do in biology today.

This is the third in a series of posts about the new National Academies consensus report, The Age of AI in the Life Sciences: Benefits and Biosecurity Considerations. I didn’t mean to take such a long break before getting back to this series, but lots of interesting developments have emerged over the last two months in AIxBio and biosecurity.

The first, an introduction and overview of the report:

The second on the “if-then” approach to AI and Biosecurity (AIxBio):

Chapter 3 and some other places in the report provide a detailed assessment of current capabilities across different levels of biological complexity.

Discussions about AI and biosecurity often blur the line between what’s possible today and what might become possible in the future. The National Academies report provides a clear-eyed assessment of current capabilities, and the distinctions matter for both policy and research priorities.

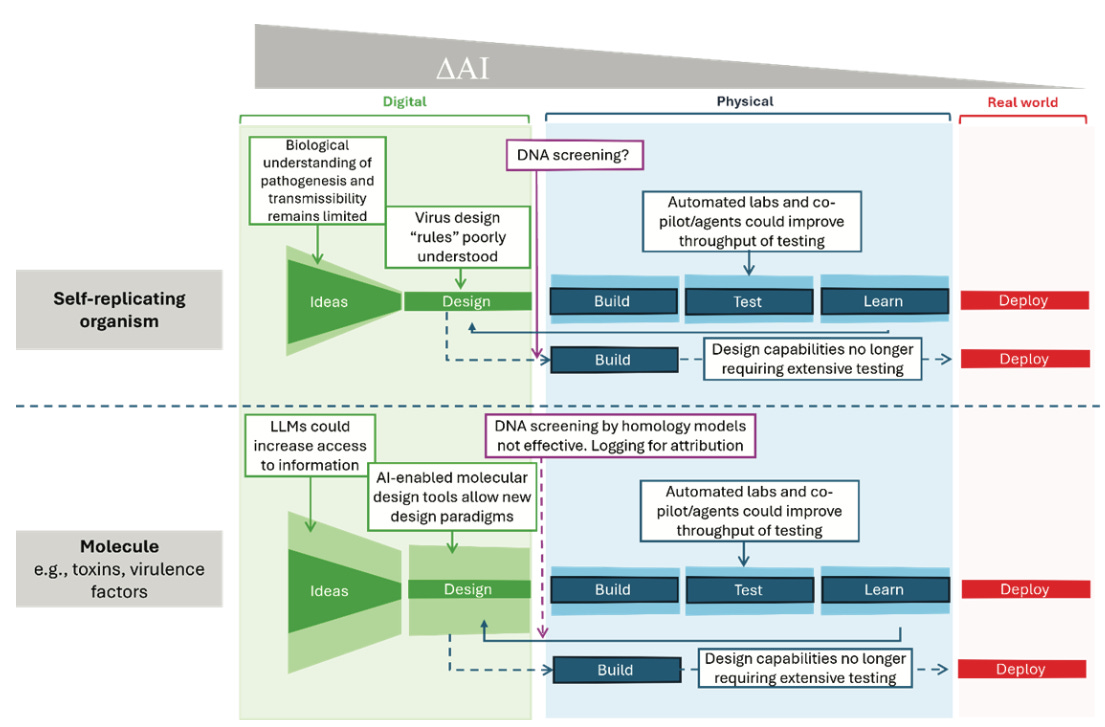

At the simplest level of biological complexity, AI-enabled tools can now design individual biomolecules with specified properties. Protein design models like RFdiffusion and ProteinMPNN can “hallucinate a protein,” i.e., generate novel protein sequences predicted to fold into desired structures. These capabilities are real and already being used to design enzymes, therapeutic antibodies, and vaccine candidates. The report notes that these same tools could theoretically be used to redesign toxins using different amino acid sequences, potentially evading simple DNA synthesis screening. This represents a genuine dual-use concern, though one limited in scope since producing and deploying such molecules still requires substantial laboratory capability.

The picture changes when considering more complex biological systems. For modifying existing pathogens to increase virulence or transmissibility, current AI models face real limitations. While some models can predict specific fitness characteristics, like antibody escape for particular viral variants, they struggle with the full complexity of pathogenesis. The report emphasizes that virulence and transmissibility emerge from networks of molecular interactions, evolutionary pressures, and host-pathogen dynamics that current models cannot adequately capture. The training data simply doesn’t exist at sufficient scale and quality to build reliable predictive models for these complex phenotypes.

Conclusion: The relative lack of biological and mechanistic understanding about virulent phenotypes and the paucity of high-fidelity biological data mean that Al-enabled biological tools currently cannot be used to de novo design and subsequently build complex biological systems that can successfully replicate as transmissible biological agents with epidemic or pandemic potential.

The most important limitation concerns de novo design of self-replicating pathogens. The report states unequivocally that no available AI tool can currently design a novel functional virus from scratch. This isn’t just a matter of computational power or model architecture. The fundamental biological knowledge and datasets required to train such models don’t exist. Viral replication involves intricate interactions between viral proteins, host cell machinery, and immune responses across multiple timescales. Capturing this complexity would require vast amounts of experimental data linking specific sequence features to replication competence, transmissibility, and pathogenesis. Such datasets are not available and would be extraordinarily difficult to generate even for research purposes.

Beyond design limitations, the report emphasizes that physical production remains a major bottleneck. AI can propose molecular designs, but building and testing them requires laboratory infrastructure, technical expertise, and iterative experimental validation. Automated laboratories might eventually reduce some of this burden, but current systems are limited in scope and reliability, particularly for complex biological assays.

These assessments matter because they help calibrate policy responses. Restrictions appropriate for capabilities that exist today differ from those needed for speculative future capabilities. The report’s detailed analysis of current limitations provides a foundation for the if-then monitoring framework, allowing policy to evolve as actual capabilities develop rather than react to hypothetical scenarios.