Tiered Access for AIxBio Governance

Parallel proposals target training data and model access to reduce biosecurity risk

Two recent publications tackle the same problem from complementary angles: as biological AI tools grow more capable, who gets to use them, and under what conditions?

NTI paper on managed access

A January 2026 report from NTI|bio by Sarah Carter and Greg Butchello proposes a managed access framework for biological AI tools themselves. The framework is built on two principles: access should be tiered according to a tool’s risk level, and security measures should be balanced against equitable access for legitimate researchers.

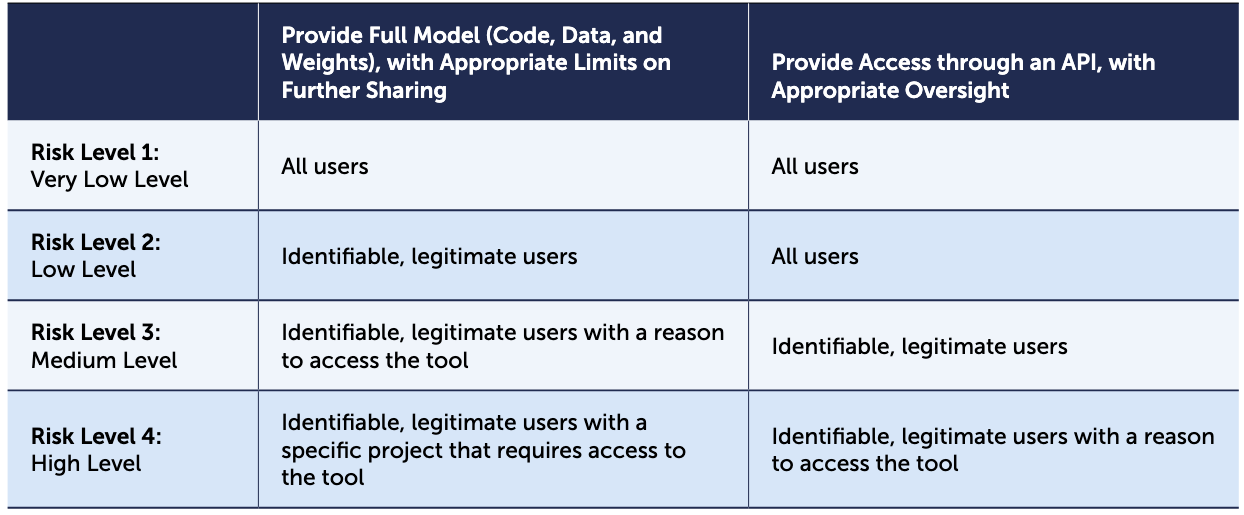

The report defines four risk levels for biological AI tools, from very low (e.g., a protein interaction predictor) to high (e.g., a model trained on high-risk pathogen genomes validated with functional data). At each level, the framework specifies what kind of user verification is appropriate, ranging from no checks at all to project-level documentation and institutional oversight. Providing access through an API rather than releasing full model weights can simultaneously broaden access and reduce risk, since the developer retains control, can monitor usage, and can maintain built-in guardrails. The report draws on case studies from national laboratories, international collaborations, and small organizations, all of which struggled with a common challenge: there are few established resources to help developers assess biosecurity risk or implement managed access in practice.

It’s a great paper, but I think it’s missing one perspective on incentives. I’m an academic. I serve on promotion and tenure (P&T) committees. P&T rewards open science: publications, open-source code on GitHub, open weights on HuggingFace. It took us years to get P&T committees to recognize the value and impact of open-source software and other products beyond the peer-reviewed publication. Most committees still won’t see “managed access release” as a meaningful contribution in the way they now (finally) recognize an open-source tool. Compound that with the long-term maintenance costs of hosting a managed service, and I worry these recommendations will struggle to gain a real foothold in the academic labs where most of the latest model development is actually happening.

Science policy forum paper

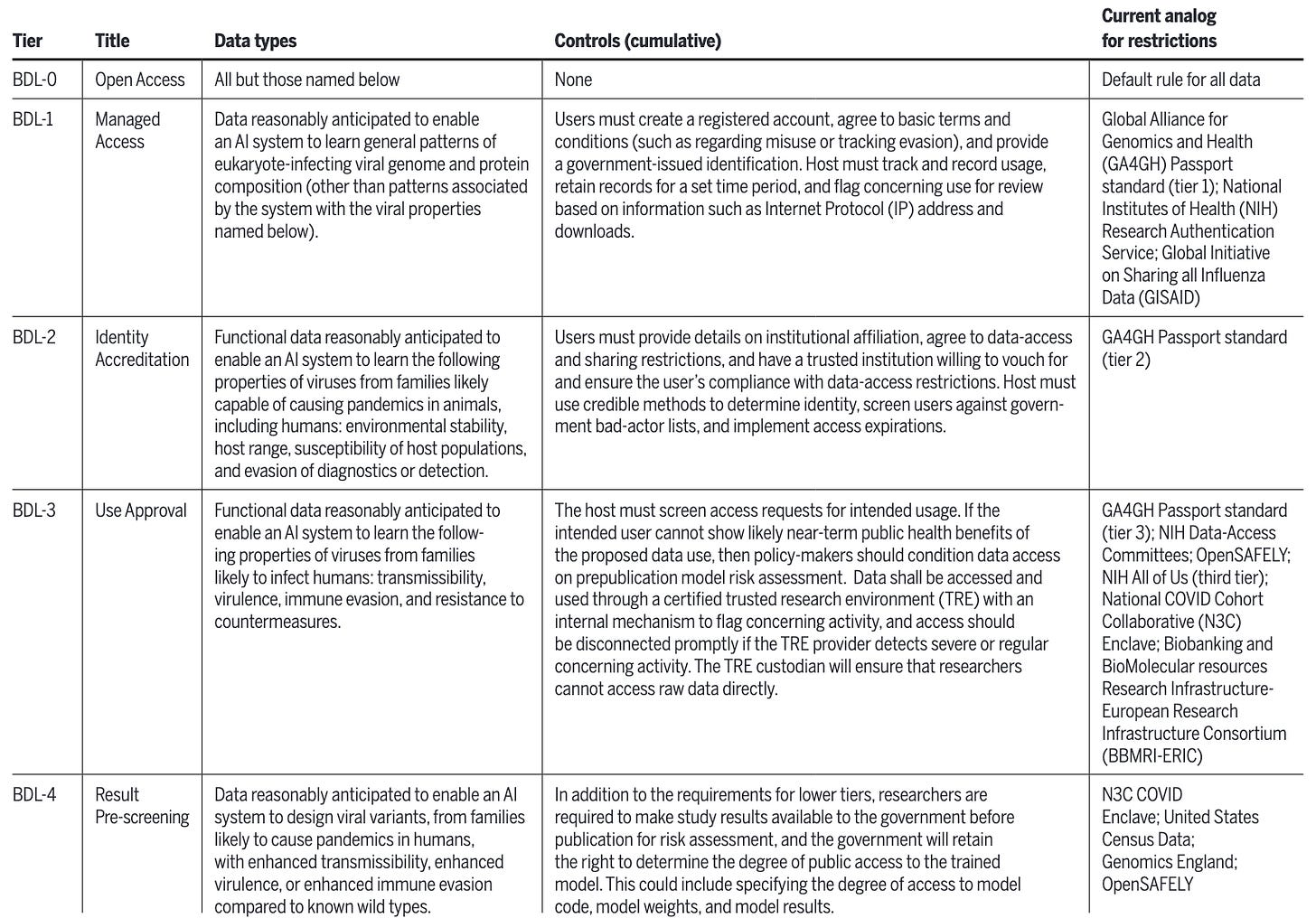

A complementary Policy Forum piece published in Science on February 5, 2026, by Bloomfield, Black, Crook, and colleagues focuses on the data side of the equation. The authors propose a Biosecurity Data Level (BDL) framework modeled on the familiar BSL laboratory classification system, with five tiers (BDL-0 through BDL-4) governing access to biological datasets based on how much they could enable concerning AI capabilities.

The core argument is that biological AI capabilities depend heavily on training data, and recent evidence supports this: ESM3 trained without viral protein data performed substantially worse on virus-related tasks, and Evo 2 showed similar degradation when eukaryote-infecting viral sequences were withheld. The authors draw on privacy precedents like NIH’s All of Us and the UK’s OpenSAFELY to argue that tiered data access is both feasible and familiar to scientists. Their proposed controls focus narrowly on new virology data, especially functional data linking pathogen genotypes to phenotypes like transmissibility, virulence, and immune evasion.

The authors do call out how such a framework might work when faced with the realities of an outbreak happening in real time, when the pressure to share data quickly and broadly can be at direct odds with tiered access controls. It’s a genuine tension, and one I’ll probably dig into in a follow-up post.

Layered defense

These two frameworks are naturally complementary. The NTI report governs who can use the tools; the Science paper governs what data those tools can be trained on.

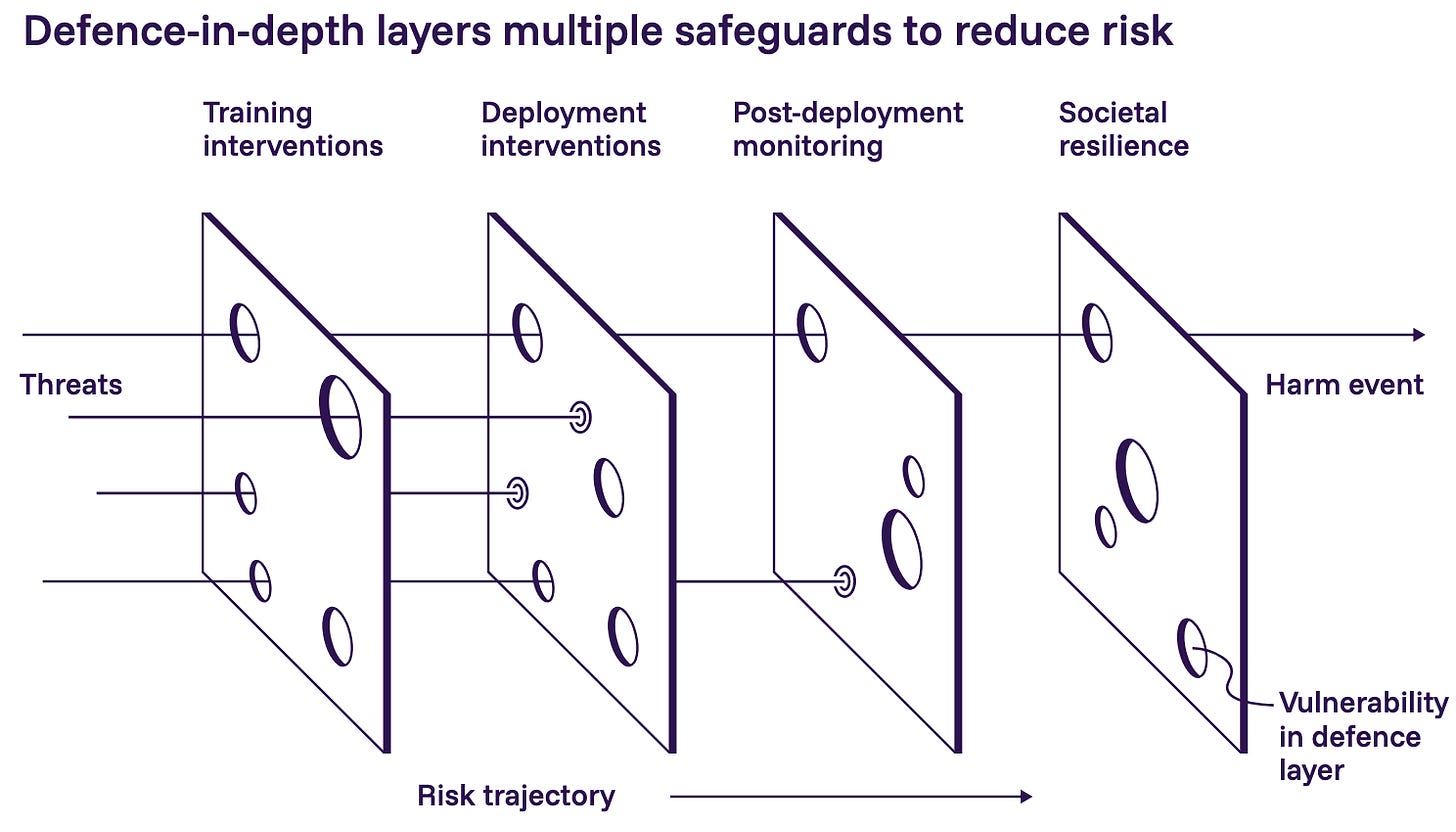

I recently wrote about the 2026 International AI Safety Report, and in this paper the authors present a “swiss cheese” model of layered defense:

Together, the Science and NTI|bio papers sketch a layered defense: control the most sensitive training data through BDLs, and control access to the resulting models through managed access tiers. Both papers emphasize that the vast majority of biological data and tools should remain open, and both call for regular reassessment as understanding of AI-related biosecurity risks matures.