Biological risk and the AI capability shift

Notes from the 2026 International AI Safety Report. 100 experts, 200 pages, 1400 references. AI co-scientist, crossing the expert threshold, industry response, dual-use, governance. 660 words / 3 min.

Yoshua Benigo led the writing of a new AI safety report, based on contributions from 100 experts. The report is over 200 pages long (with 1,451 references!) and describes the full range of risks that general-purpose AI presents.

The section on biological risks starts on page 64 (2.1.4. Biological and chemical risks).

AI biological risks: what changed between 2025 and 2026

The past year has seen a fundamental shift in AI’s relationship with biological research. While the 2025 report documented concerning capabilities, the 2026 report reveals that these concerns have materialized into concrete developments that are reshaping both opportunities and risks.

The AI co-scientist

I’m still a skeptic on this front, but the report argues that a significant development since last year is the emergence of true AI “co-scientists.” The report argues that these systems can now meaningfully support top human scientists and independently rediscover novel, unpublished scientific findings.

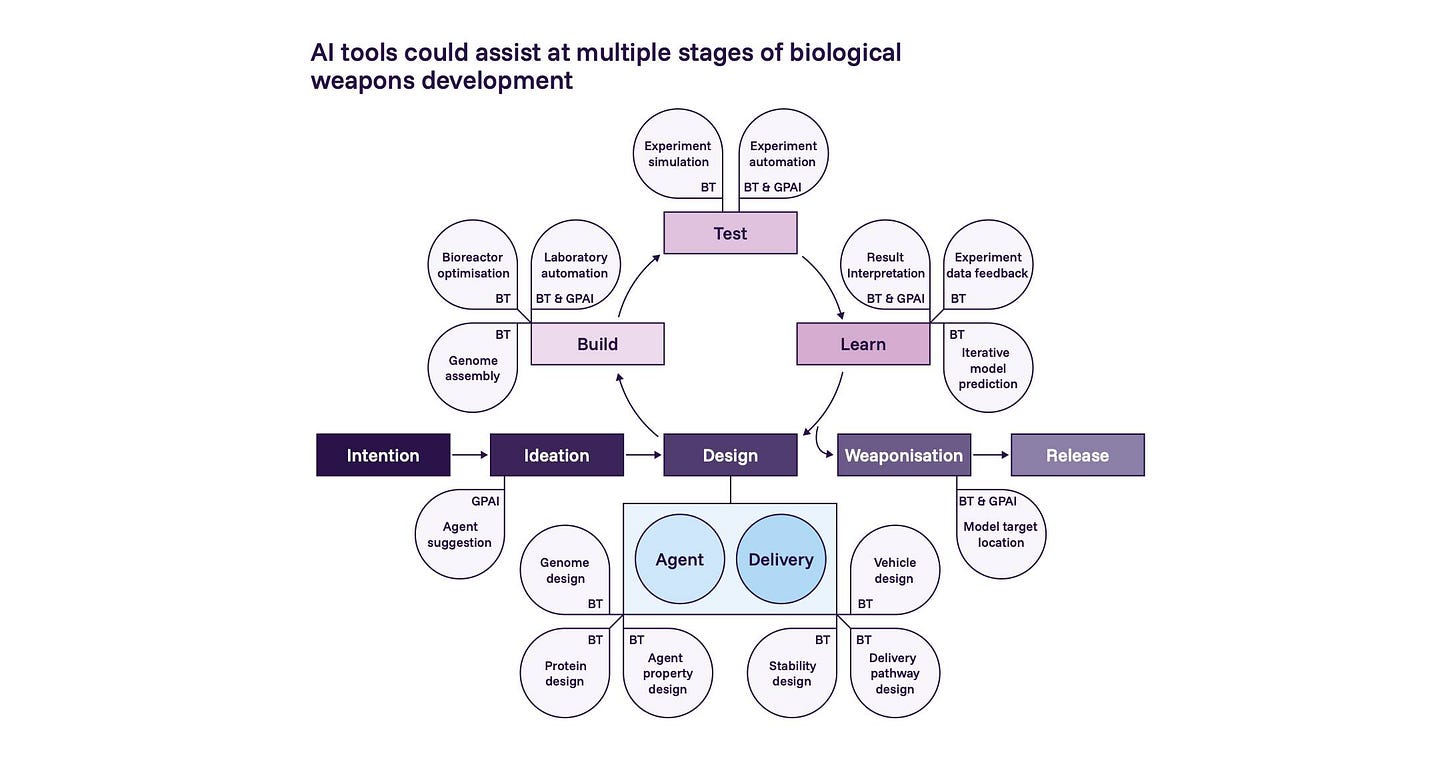

Since the publication of the previous Report (January 2025), AI ‘co-scientists’ have become increasingly capable of supporting scientists and rediscovering novel scientific findings. AI agents can now chain together multiple capabilities, including providing natural language interfaces to users and operating biological AI tools and laboratory equipment.

Multiple research groups have deployed specialized scientific AI agents capable of performing end-to-end workflows, including literature review, hypothesis generation, experimental design, and data analysis.

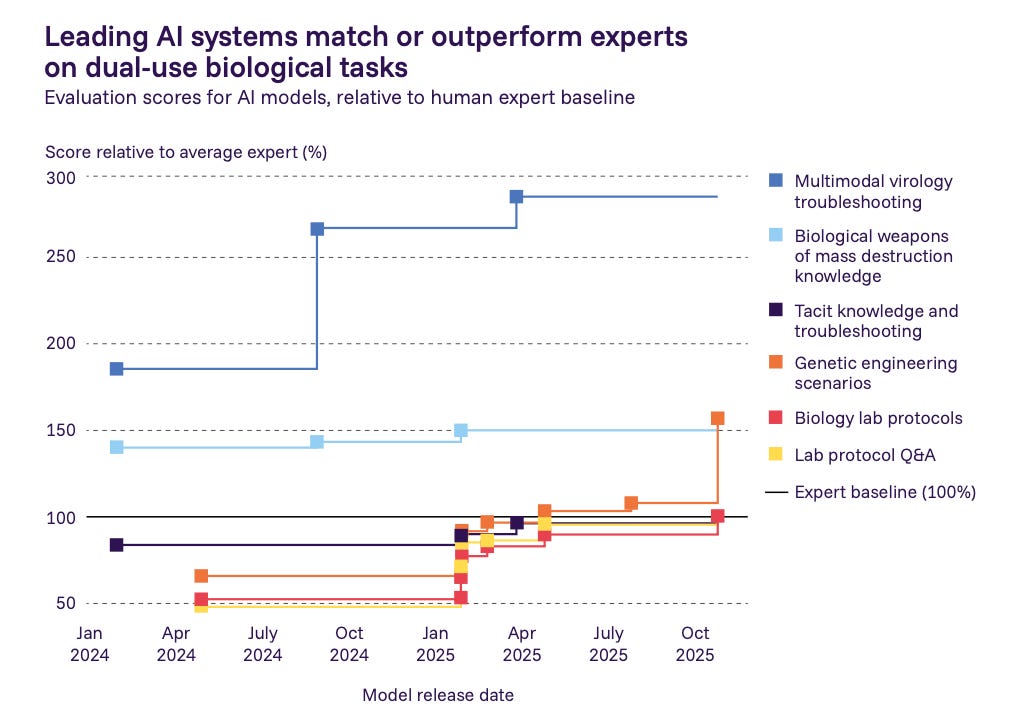

Crossing the expert threshold

Leading AI systems now match or exceed expert-level performance on benchmarks measuring knowledge relevant to biological weapons development. OpenAI’s o3 model, for instance, outperforms 94% of domain experts at troubleshooting virology lab protocols. This represents a qualitative leap from providing information to providing the kind of tacit, hands-on knowledge that previously required years of laboratory experience.

We’ve also seen the first instance of genome-scale generative AI design, where researchers used biological foundation models to generate a significantly modified virus from scratch (though crucially, it infects bacteria rather than humans). This proof of concept demonstrates capabilities that simply didn’t exist a year ago.

Industry response

For the first time, all three major AI companies (OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google DeepMind) released models with heightened safeguards specifically targeting biological risks. They couldn’t rule out that their models could meaningfully assist novices in creating biological weapons, so they implemented additional filters and restrictions. This marks a shift from theoretical concern to operational precaution.

OpenAI: Preparing for future AI capabilities in biology

Anthropic: Activating Al Safety Level 3 Protections (pdf)

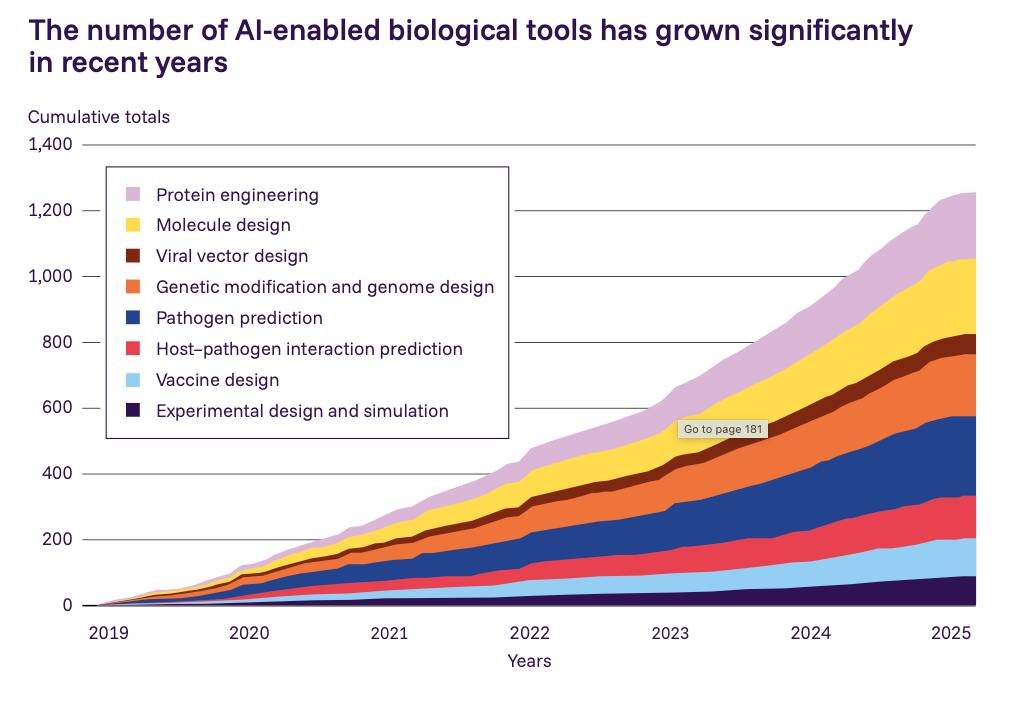

The dual-use dilemma intensifies

The challenge has become more acute: 23% of the highest-performing biological AI tools now have high misuse potential, and 61.5% of these are fully open source. Meanwhile, only 3% of 375 surveyed biological AI tools have any safeguards at all. The number of AI-enabled biological tools has grown exponentially, with natural language interfaces making sophisticated capabilities accessible to users without specialist expertise. This creates a difficult choice for policymakers: the same tools accelerating beneficial medical research can be repurposed for harm. And unlike large language models, most biological AI tools are already open-weight, making meaningful restrictions nearly impossible without hampering legitimate research.

Looking forward

The trajectory seems pretty clear to me: AI capabilities in biological research are advancing faster than our ability to govern them. The gap between what’s possible and what’s safe continues to widen, with technical safeguards lagging behind both general-purpose and specialized biological AI systems. Yet simply restricting access risks sacrificing the enormous potential benefits for drug discovery, disease diagnostics, and pandemic preparedness.

The international community faces an important task: developing frameworks that can distinguish between legitimate scientific inquiry and malicious intent, while recognizing that the same AI systems capable of designing novel therapeutics can, with minimal modification, design novel pathogens. This isn’t some theoretical future risk. It’s a present-day governance challenge that demands coordinated action, backed by empirical research and wet lab studies on the real impact of AI on human uplift.

Excellent summary of the biologcal risk section. The stat about only 3% of 375 biological AI tools having any safeguards is pretty alarming when you pair it with 61.5% being fully open source. The governance lag is real and its hard to see how traditional regulatory frameworks can keep pace when capabilites are advancing this fast. The dual-use challenge feels fundementally different from past tech risks too.