Rubrics, Not Vibes: Consistency as a Feature in Peer Review with AI

Responsibly using AI for a structured manuscript / grant proposal review can reduce reviewer variance while keeping human judgment central. Bonus: a prompt I use for my own draft proposals.

I just finished reviewing 18 grant proposals across two different funding organizations, one public one private. And I have three journal peer review requests sitting in my inbox I need to get to.1

Peer review of manuscripts and especially grant proposals is one of the highest-impact service activities we do in academia. Publications are important, and grant proposal decisions can make or break a career. We treat these like careful measurements, but perform the activities as humans, with all our human faults, foibles, and biases.2

And we’re often doing this under immense time pressure: while peer review is a required service activity it isn’t part of our “job” in the same way as teaching courses, writing grants, writing papers, and mentoring students. All of which is why…

I’m not 100% confident in my reliability as a reviewer

I spent most of my weekend reviewing these proposals, writing reviews, and waffling between integers on a scoring matrix. Time for an uncomfortable confession. Maybe this stems from the crippling imposter syndrome we all deal with.3

I don’t have 100% confidence in the comparative judgments I just made.

I don’t know if I would have made the same calls if the order was shuffled or you caught me on a different day.4 I know my scores were influenced by whether a proposal landed early or late in the stack. I know my assessment shifted along with the level of my coffee cup, how long I’d gone since my previous meal, and if I were doing this on a work day whether my calendar was miraculously clear or packed with back-to-back meetings.5 The proposals themselves didn’t change, but my capacity to evaluate them fairly did.

Most academics I know recoil at the suggestion of using AI for manuscript or proposal review.6 The reaction is visceral. Something about it feels wrong, inauthentic, maybe even lazy (see further below on this one). But here’s what I’ve been thinking: we humans might actually be far more biased than these AI models, and our judgments are demonstrably unreliable and highly variable.

It’s not just me.

Paul Bloom recently posed a provocative question: is it irresponsible for academics to refuse to use AI if it would improve the quality of their work?

Paul talks about writing papers with AI assistance. From the essay:

Suppose a human remains the author, but AI helps write the paper—it’s involved in brainstorming ideas, clarifying arguments, identifying the relevant literature, anticipating objections, tightening prose, and so on.

Is there anything wrong with this?

If you think using AI will make the paper worse, then it’s obviously wrong to use it, just as it would be wrong to intentionally use a malfunctioning statistical program. But suppose that AI will make a paper better. (What’s “better”? For present purposes, imagine a blind assessment: experts compare a version created alone versus one created with AI; whichever is judged better is better.) Whether or not we’re already there, it’s easy to imagine a future where this is true.

There’s nothing wrong with using AI in these circumstances. In fact, if an author could improve a paper by using AI, it would be irresponsible not to do so. What would you think of someone who decided to use the second-best statistical test, who purposefully did a shoddy literature review, or who had the chance to get sharp and useful comments on the paper’s arguments and chose not to? That’s just bad scholarship.

Michael Inzlicht went further, admitting after evaluating 200 job applications that he had little confidence in his own judgments and wondered whether declining to use AI was actually the responsible choice.

From Michael’s essay:

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: I have little confidence in the quality of my comparative judgments, even in my grading of a pile of student papers. I know my evaluations are skewed by whether a candidate came first or last in the pile, whether I am in a good mood or nursing a headache. I usually get a feeling about a paper or candidate and then just go on vibes. I’ve been doing this for decades, and every time I finish, I’m left with the nagging feeling that I’ve made tons of mistakes or that I have been unfair. Yet we trust humans like me to do this kind of work. And some of us would be horrified if we learned that a colleague outsourced some of this work to AI

Yet, if I had a well-written rubric with specific criteria, I’m pretty sure AI would do a better job than I would. It would be more consistent, less biased by irrelevant factors, and certainly not influenced by whether the Eagles are playing on the radio while it’s grading.

Both are wrestling with the same discomfort in that human evaluation, for all its supposed gold-standard status, is messy, inconsistent, and riddled with biases that have nothing to do with the work being evaluated.

Empirical evidence emerging

A recent preprint posted last week by Booeshaghi, Luebbert, and Pachter provides the first (to my knowledge) large-scale empirical comparison of AI and human peer review.

Booeshaghi, A. S., Luebbert, L., & Pachter, L. (2026). Science should be machine-readable (p. 2026.01.30.702911). bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.64898/2026.01.30.702911

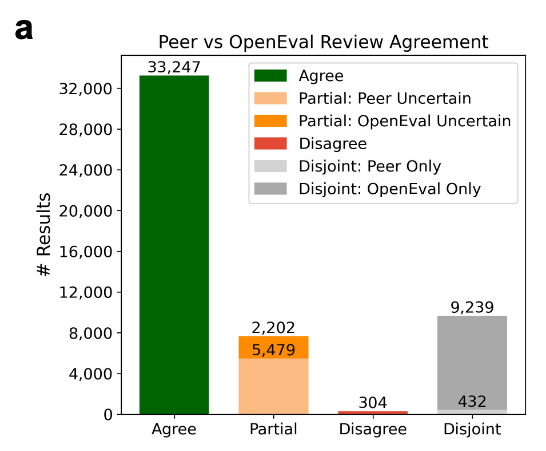

Their framework, OpenEval, extracted nearly 2 million claims from 16,087 eLife manuscripts and compared AI-generated evaluations against human reviewer assessments. When both AI and human reviewers evaluated the same research results, they agreed 81% of the time. Outright disagreement occurred in only 0.7% of cases.

The AI system assessed 92.8% of claims in a manuscript on average, while human reviewers were more selective, covering only 68.1%. This suggests AI isn’t replacing human judgment so much as extending its reach.

Notably, agreement was highest when claims were grounded in data or citations, and lowest for claims based on inference or speculation. In other words: rubrics, not vibes.

Rubrics, not vibes

Consider what happens when we have detailed, well-articulated evaluation criteria. You know, a proper rubric with specific metrics and standards. In these circumstances, I agree with Paul and suspect AI would evaluate proposals and manuscripts more fairly and consistently than I might. The OpenEval data discussed above kind of shows this: when evaluation criteria are explicit and claims are grounded in data, AI and human reviewers converge. The divergence comes in where rubrics end and vibes begin.

The model won’t favor the proposal it read right after lunch, or unconsciously weight eloquent writing over technical rigor just because it’s been a long day. It won’t be swayed by institutional prestige or whether the PI’s writing style happens to match its own preferences. So, reiterating Paul’s provocative question:

It is irresponsible and unethical not to use AI where AI might improve a comparative judgment?

I’m not advocating that we should hand over the entire review process to algorithms and walk away. In fact, I wrote on this very newsletter a few months ago about how you could easily sway an AI review one way or another by simply altering your prompt.

Human judgment remains essential, particularly for assessing novelty, evaluating the feasibility of proposed approaches in context, and making nuanced calls about scientific merit that require deep domain expertise and experience. We need humans to identify what AI might miss: the creative leap that doesn’t fit neatly into rubric categories, the ambitious proposal that might fail spectacularly or succeed brilliantly, the methodological innovation that established criteria can’t yet capture.

But for the systematic evaluation against stated criteria? For ensuring that every proposal gets the same careful attention whether it’s first or 50th in the queue? For reducing the noise introduced by reviewer fatigue, mood, and arbitrary factors? AI could make the process faster, more transparent, and meaningfully fairer.

The question isn’t whether AI is perfect. It is not (yet at least). It’s whether AI-assisted review, with clear rubrics and maintained human oversight, might actually serve grant applicants and authors better than the current system where we pretend that human judgment alone is somehow more objective than it actually is.

The case against AI review

Not everyone is convinced, and strong objections deserve engagement. Writing in Times Higher Education, Akhil Bhardwaj argues that “AI is not a peer, so it can’t do peer review.” His core claim: a peer is not merely an error-detector but someone who inhabits the same argumentative world as the author, who recognizes the paper as situated in a field’s live disputes and vulnerabilities.

Bhardwaj writes that AI tools “do not wrestle; they process.” They can mimic a referee’s report but have no stake in whether a finding is true or a method convincing. Science, he argues, is not only a body of results but a culture of argument, and the reviewer who is “late because they are genuinely unsure” embodies a kind of care that metrics cannot capture.

This is a serious objection, and I think it’s partly right. The Booeshaghi study found that AI and humans diverged most on claims involving inference and speculation, exactly where Bhardwaj’s “argumentative world” matters most. AI excels at systematic evaluation against stated criteria. It struggles where the task requires recognizing that an ambitious proposal might fail spectacularly or succeed brilliantly, or that a methodological innovation doesn’t fit neatly into existing rubric categories.

But here’s my pushback: Bhardwaj’s idealized peer reviewer, the one who wrestles and cares and is willing to be persuaded, is not the median reviewer.

The median reviewer is tired, overcommitted, and influenced by whether the proposal landed first or fiftieth in the stack. The interesting question isn’t whether AI matches the best human review. It’s whether AI-assisted review with clear rubrics outperforms the inconsistent, fatigue-influenced, mood-dependent review we actually get.

The laziness factor

I think there’s a real concern distinct from Bhardwaj’s philosophical objection, and it came from a colleague who reviewed a draft of this post.7 The worry is not that AI will replace human judgment, but that it will give us permission to stop doing the work.

You get your favorite tool to summarize a PDF you haven’t read (or write a tool to do this for you). You ask it to show the strong and weak points of a paper you haven’t engaged with yourself. An editor asks ChatGPT to summarize the three reviews they received and recommend rejection or minor revision. Let’s call it the laziness factor.

I don’t like engaging with slippery-slope arguments, but I think this one’s real. Everything I’ve argued above assumes that the human reviewer actually does the reading, the thinking, the hard work wrestling with the manuscript or grant proposal that’s the core of peer review. AI as a rubric enforcer only works if the human has independently formed their own assessment first. I don’t want AI to become a shortcut to the appearance of engagement; if this happens I think we’d have made things worse, not better.

But here’s a counterpoint to the counterpoint: the laziness factor is not unique to AI. Reviewers already phone it in. We’ve all received the two-sentence review that reads like the reviewer skimmed the abstract, or the worst IMHO - a reviewer who reviews the paper he/she wanted to see, rather than the paper I submitted.

I suggest that the question is whether structured AI integration, done right, with the reviewer submitting their own assessment before seeing the AI review, actually raises the floor of engagement by making low-effort reviews visible. When your assessment diverges sharply from the AI’s on basic rubric criteria, that discrepancy is itself a signal, and one that an editor can (and should!) see.

As my colleague who reviewed a draft of this post put it: bots can be very useful the same way a sharp young intern is useful. You listen to them, but you think to yourself, did they read that paper well, or did I not write it properly? That engagement is the whole point.

I’m writing a paper on this, and I’m looking for reviewers

I recognize the irony of me writing this essay about vibes and objectivity, based purely on personal vibes and subjectivity. Since drafting this post, I’ve done some of the work: I’ve dug into the empirical and philosophical literature, found collaborators with complementary expertise, and drafted a position paper. The Booeshaghi preprint and Bhardwaj essay that I discussed above come at this from different angles, and I think both make very good points. What’s missing was a framework for deciding when AI-assisted review is appropriate (systematic rubric evaluation) versus when human judgment remains essential (novelty, feasibility, creative leaps). We’ve proposed one. The paper will have a similar title to this one (“Rubrics, Not Vibes: AI-Assisted Quality Control in Academic Peer Review” or something close to it) with two interested and engaged collaborators: one a physician scientist, another an AI/bio researcher. A preprint will land on SSRN shortly, and we’ll submit it for peer review shortly after that.

And I’ll be looking for peer reviewers. If you have expertise or strong opinions on peer review, science policy, AI in scholarly communication, or the measurement properties of expert evaluation, I would love to recommend you as a reviewer. I’m not looking for friendly reviewers who will rubber stamp the “accept without revisions” button and tell me this is great.8 I’m looking for people who will tell me where the argument is weak, where the evidence doesn’t support the claim, where I’ve been unfair to the counterarguments, or where I’ve missed something important. The kind of reviewer Bhardwaj describes: one who wrestles with the work long enough to care.

And if you use AI after your own first-pass reading and engagement to sharpen your feedback, I’m not even mad. In fact, I’d consider it a proof of concept.

If you’re interested, my email address is easy to find.

Bonus: A prompt I use to review my own proposals

I’m collaborating on an R01 to submit to NIH. With my collaborators’ permission, I used both GPT-5.3 with extended thinking, as well as Claude Opus 4.6 with extended thinking, prompting both to act as a study section reviewer on my proposal draft.

The mock study section reviews I got back from both models mostly agree, and I have to say they were extremely useful. We’re still going to ask several human colleagues, both clinical physician-scientists as well as genomics / data science folks to internally review our proposal before submitting.

You are an NIH study section reviewer serving on an NHLBI R01 panel, with specific experience reviewing applications for the Pulmonary Injury, Remodeling, and Repair (PIRR) study section.

Your task is to conduct a rigorous, critical, and realistic NIH-style peer review of the following R01 proposal. Review it exactly as you would for a real study section, following NIH scoring conventions, tone, and structure.

Assume:

- This is a standard R01.

- The PI is a competent, well-trained investigator.

- The proposal is scientifically plausible but not presumed to be excellent.

- You should actively look for weaknesses, ambiguities, and risks that would realistically affect enthusiasm and score.

=== REVIEW FORMAT REQUIREMENTS ===

1. **Overall Impact**

- Write a concise but substantive paragraph explaining the likelihood that this project will exert a sustained, powerful influence on the field.

- Clearly balance strengths and weaknesses.

- Make explicit what prevents this from being “outstanding” if applicable.

2. **Scored Review Criteria**

Provide a separate section for each of the five NIH criteria:

- Significance

- Investigator(s)

- Innovation

- Approach

- Environment

For each criterion:

- List **Major Strengths** (bulleted)

- List **Major Weaknesses** (bulleted)

- Be specific and technical where appropriate.

- Avoid vague praise; use language typical of NIH critiques.

3. **Approach Section Expectations**

In the *Approach* critique, explicitly comment on:

- Rigor and feasibility of experimental design

- Statistical considerations and power (or lack thereof)

- Biological and technical risk

- Alternative strategies and contingency planning

- Whether aims are overly ambitious or insufficiently integrated

- Alignment of methods with the stated hypotheses

4. **Additional Review Considerations**

Include brief comments on:

- Rigor and Reproducibility

- Biological Variables (e.g., sex as a biological variable, where relevant)

- Authentication of key biological and/or chemical resources

- Data sharing and resource sharing plans (if mentioned or implied)

5. **Protections / Human Subjects / Vertebrate Animals**

- If applicable, note whether these sections are acceptable, inadequate, or raise concerns.

- Do not invent fatal flaws, but flag omissions or superficial treatment.

6. **Summary Statement Style**

- End with a short “Resume and Summary of Discussion” paragraph, written in the voice of a SRO-generated summary.

- Clearly identify the **primary drivers of the score**.

7. **Preliminary Overall Impact Score**

- Provide a **single integer score from 1 (exceptional) to 9 (poor)**.

- Justify the score in 1–2 sentences.

- Be conservative and realistic; default scores for solid but imperfect R01s are often 4–6.

Finally, briefly note whether this application would likely fall above or below the current NHLBI payline, assuming a typical funding climate.

=== TONE AND STYLE GUIDANCE ===

- Use NIH-typical language (e.g., “The enthusiasm is tempered by…”, “A significant weakness is…”, “While the premise is compelling…”).

- Be fair but not generous.

- Do not offer coaching or rewrite the proposal unless explicitly asked.

- Assume this critique will be read by the PI after summary statements are released.At least one of these I’m really excited about! It’s rare that I get excited about writing a peer review report/recommendation.

Lots of ink has been spilled about bias in AI, but we humans are far better at being biased than your favorite frontier AI du jour.

And if you never question your confidence in your own comparative judgment and you never feel the burning sensation of imposter syndrome, perhaps you’re dealing with a touch of a different cognitive bias.

The day I performed most of this review we were snowed in by terrible weather that rocked the US East Coast. My lovely wife flew down to Mexico City for the week. My kids were out of school for the week, and needed lunch, dry boots, a judge+jury for 1,000 minor injustices, batteries for the VR controllers, and help with a million other things.

This isn’t unique to us as academics. I think most people have heard of this study looking at parole decisions made by judges finding that parole decisions started out more positive, but approached 0% as the day went on and the judge got hungrier. You can read more about this at: Danziger, Shai, Jonathan Levav, and Liora Avnaim-Pesso. “Extraneous factors in judicial decisions.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108.17 (2011): 6889-6892. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1018033108.

At least publicly. What my closest friends admit to doing in private clashes with the public swearing off of AI for peer review that you usually hear.

Thanks - you know who you are.

That said, if your Bluesky timeline is filled with dismissive and thoughtless anti-AI hype, it’ll be a hard pass. I’m not looking for a rubber stamp, but I’d like genuine and thoughtful engagement with my arguments on the merits.

Update: here's the preprint:

Rubrics, Not Vibes: Structured AI Integration as Quality Control for Peer Review by Stephen Turner, Agnieszka Swiatecka-Urban, Arjun Krishnan :: SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=6314421