Pick a License, Not Any License

Why you should care about data science software licenses and how to learn more

VP (Pete) Nagraj is a long time friend, colleague, and collaborator, and is the author of this post. Pete and I have co-authored over a dozen publications, and have taught several graduate courses in data science together. Pete leads the health security analytics / infectious disease modeling and forecasting group at Signature Science, where we worked together for several years. He is also currently a Ph.D. candidate at the UVA School of Data Science.

In the data science world, “free,” “open,” and “available online” often get used interchangeably. Whether we’re writing quick scripts, sharing notebooks, building packages, distributing trained models, or even designing whole programming languages, we’re constantly making choices about what stays open and what gets restricted. In practice, those decisions usually come down to something deceptively simple: the software license. But as both users and developers of data science tools, how often do we actually stop to consider the licenses that come with them?

Think about this:

When you find a new piece of software to use, what is the first thing you look for?

When you’re writing your own tool, what is the first thing you include in the code repository?

The answer to either question probably isn’t the license. At best, data scientists tend to consider reviewing or selecting a license as a dry, procedural step and slide into a “pick a license, any license” mindset. Worse? Maybe they overlook licenses altogether.

Choosing a license is the moment when we define the boundaries of access to the data science tools we create. It may not always be up to you as an individual to decide how those tools are licensed. But you can still understand the role licenses play and, most importantly, respect the boundaries others have set.

This post attempts to encourage that mindset. It starts with a brief look at licensing practices among data science package maintainers in the wild, touches on recent changes to the Anaconda terms of use, and ends with a few resources for digging deeper.

Before going further, the usual disclaimer: I am not a lawyer, and nothing here should be taken as legal advice. I’m also absolutely not suggesting that something “free” lacks value or that paid software is inherently better.

What follows is intended as an origin, not a destination. Read more. Learn more. Take ownership and usage rights for data science tools seriously. There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Don’t just pick any license.

Licenses on CRAN

R code can be distributed as a package, and the Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN) acts as a centralized repository for openly sharing packages. CRAN makes binaries and source code for all contributed packages publicly available. So, by definition, all CRAN packages are source available.1 But that doesn’t mean they are all open-source, licensed under the same terms. CRAN contributors are required to specify a license when uploading a package, and those licenses vary.

To illustrate data science licensing in the wild, we can look at licenses on CRAN. Metadata for CRAN packages is easily accessible thanks to the tools::CRAN_package_db() function. After retrieving a snapshot of CRAN2 data, I aggregated the licenses of all packages to look at the distribution of license types, with an eye towards discovering how many licenses were copyleft3 and/or prohibiting commercial use.

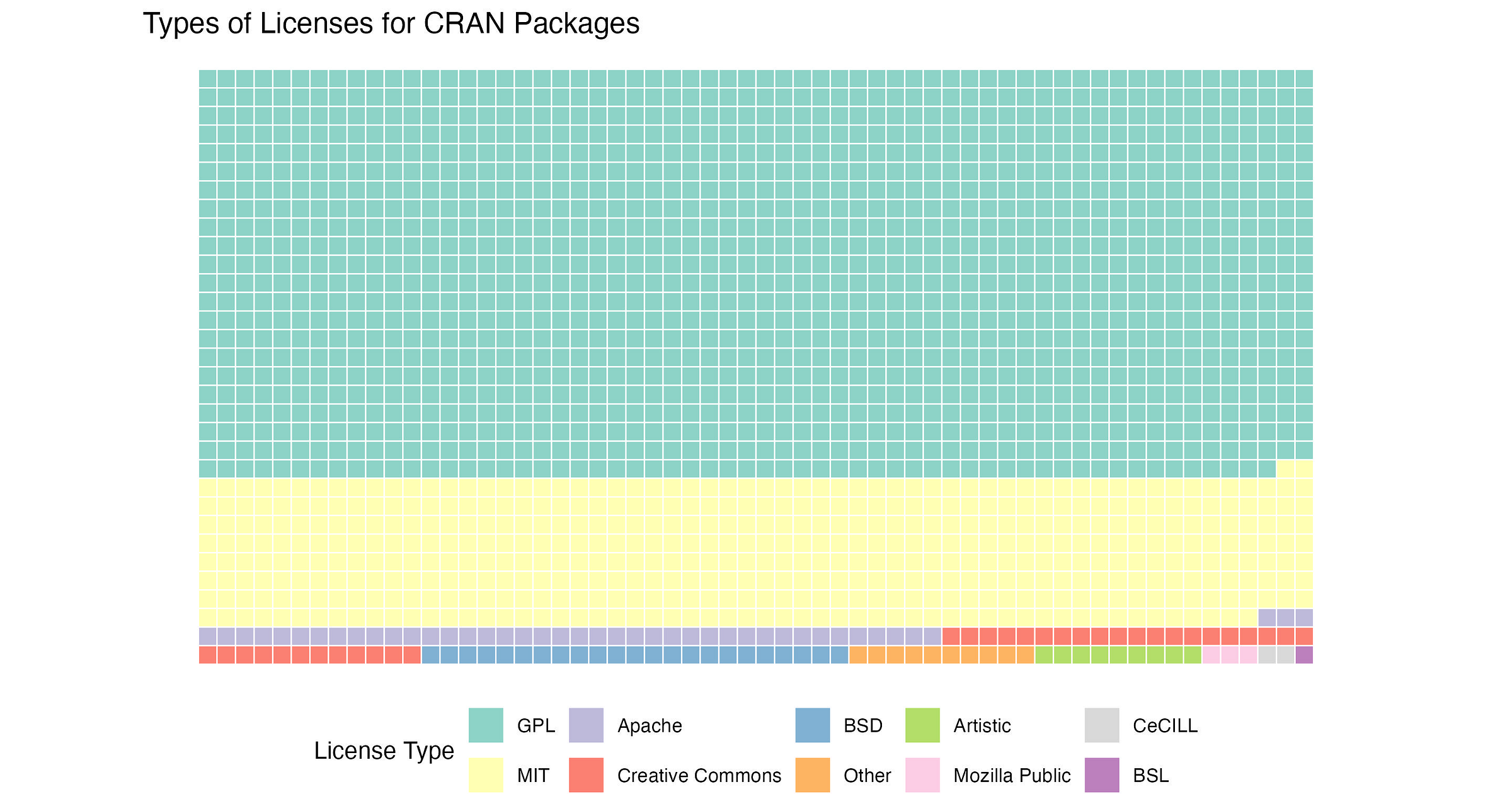

CRAN enforces some degree of conformity in how package maintainers refer to licenses. That said, for this project the licenses needed a bit of reconciliation. I applied a few simple rules to aggregate the results to a set of license types. For example, I reduced flavors of the GNU General Public License (e.g., GPL-2, GPL-3, LGPL) to a “GPL” license type. Another example was the Creative Commons licenses, which I aggregated irrespective of the individual elements (Attribution, ShareAlike, etc) for the analysis of high-level license types. Across the 23,202 packages in CRAN, I found 9 principal license types: GPL, MIT, Apache, Creative Commons, BSD, Artistic, Mozilla Public, CeCILL, and BSL. The handful of stray and/or ambiguous4 license types were pooled into an “Other” category.

The vast majority of licenses are either some form of GPL (68.7%) or MIT (24.9%). The next most common types are Apache (2.2%), Creative Commons (1.7%), and BSD (1.2%). The remaining license types make up a long tail. The figure below illustrates the relative proportion of the license types we defined.

We can also look at how many of the licenses are characterized as copyleft and/or non-commercial. Again, using some simple rules on the specific licenses (not the aggregated license types), I counted up the number of copyleft and non-commercial instances. I considered anything that was GPL, Mozilla Public License, EUPL, CeCILL, or contained a Creative Commons ShareAlike attribute as copyleft. Given the predominance of GPL, it’s probably not too surprising to see that the majority of the licenses on CRAN, roughly 7 in every 10, are copyleft.

To figure out which licenses prohibited commercial use, I looked for indications of non-commercial use in the license name or those that were clearly marked as Creative Commons with a NonCommercial attribute. Out of >23,000 package licenses, only 18 in total fit these criteria. That’s <0.1%.

So what does this all tell us? For one, there are clearly dominant patterns in how packages are licensed. Developers looking to adapt R packages should be aware that most of the dependencies for any given package are likely to carry copyleft terms. That said, explicit non-commercial terms don’t seem to be as widely used. This kind of context is particularly relevant for those looking to commercialize products that have dependencies drawn from CRAN.

A final thought: there seems to be an alignment between the predominant types of licenses and the license templating feature in usethis, which is an extremely popular5 utility for package developers. The usethis license options include several types of GPL, MIT, Creative Commons, and a proprietary template.6 While it may be difficult (or impossible) to prove cause and effect, I think there are some interesting threads to pull regarding the “convenience factor” when it comes to specifying licenses. Are CRAN package maintainers carefully considering terms of use? Or are they leaning on the tools at hand to casually apply a license?

What Just Happened with Anaconda

Licenses don’t just dictate terms of use for individual packages. In fact, they can be applied as a blanket to control how entire repositories are used. As data scientists, the software repositories we rely on are typically coupled to how we manage environments. For example, while many Python packages are accessible via PyPI and Anaconda, there is a degree of ergonomics with configuration that may push developers towards one repository or the other. Installation time alone can drive users to new package managers.7

It’s hard to beat convenience. But if repositories include blanket terms of use, then you should be aware of what that license might mean for your use-case. The recent changes to Anaconda offer a perfect case study of exactly why this matters.

First, a primer for those who may not be familiar.

Anaconda is one of the largest distribution platforms for Python and R packages. Anaconda, Inc. maintains the Anaconda installer and Defaults package channel. While there are other popular “community channels” (e.g., conda-forge), as its name suggests, the channel maintained by Anaconda, Inc. is the default when users try to install packages.

In 2020, Anaconda introduced a commercial terms-of-service model for its package repository. Under these terms, organizations with more than 200 employees are generally required to purchase a license to download packages from the Anaconda-maintained Defaults channel. Over the past several years, updates and enforcement changes have brought renewed attention to these policies, prompting questions, explainers, and workarounds across the data science community.8

On its face, the licensing change might seem natural. After all, why shouldn’t a “large company” pay for a service?

But the initial changes purely categorized organizations by number of employees, which led to some legitimate confusion about what kinds of organizations were subject to the new terms. In July 2025, Anaconda updated their license again. The current terms now indicate that certain non-profit organizations and academic institutions may be exempt from the commercial license requirements.9 However, a shift back may not recapture the users from academia and non-profits who might have pivoted away from Anaconda.

For companies that aren’t exempt, this licensing change can present real challenges. Of course, the easy button is to pay for a commercial license. But that may be hard to justify for smaller data science teams. It also assumes that the organizations know they need the license. Organizations would either need to already be aware of all users’ package management behaviors or conduct a thorough discovery process. That would potentially extend to legacy workflows too. If older software relied on any Anaconda-owned channels and had to be rebuilt, it would require a commercial license. There may be situations, whether through transition of contracts or by virtue of using other open-source tooling, where there is a sort of shadow inheritance of configurations that now require a license. And lastly, in our brave new data science world, what does this mean for code written by agents that are acting on behalf of a large company? How can/should someone guard against those potential violations?

What might feel jarring for these commercial users is that another company, Anaconda, Inc., so abruptly asserted their prerogative to charge for their service. And if you do think about Anaconda as a service, that may sound strange. It’s common for services to be piloted as free then shift to paid subscription models. But is Anaconda a service or a repository?

If we think about Anaconda as a repository, then let’s remember what it contains: individual packages that, like CRAN and other repositories, may be released under any manner of open-source licenses. The contributors of the packages that are the reason why Anaconda is able to provide a service were not involved in updating the Anaconda terms. They aren’t directly benefiting from the commercial fees either.

As important as it is for data science users to be aware of repository-scale licenses, it’s also critical for developers to understand who controls the infrastructure their tools depend on, and under what terms.

How to Learn About Licenses

The goal of this post is to inspire appreciation, and maybe even some interest in licensing. As I said up front, it’s a starting point. So how can you learn more about licenses?

I’d recommend beginning with the tools you rely on the most. What licenses do they use? Have they changed over time? If so, is the rationale for updates to licensing documented in the README or changelog? Starting there will help ground what you learn in how it can directly impact your work.

For a next step, find some of the resources that are available to explain licenses to developers. There are a lot! And it’s not all legalese. In fact, many of these resources deliberately try to frame licensing in plain language. I’ve included a few examples here, with descriptions, links, and a note about who created each guide. While all of these are developer-facing and try to avoid lawyerspeak, they still might carry biases that you should be aware of when deciding how to navigate licensing in your own projects.

A dev’s guide to open source licensing: An approachable (and brief) primer on open-source software licensing published by GitHub’s The ReadME Project. The post narratively steps through motivations for licensing, basic terminology (e.g., copyleft vs permissive), and includes a perspective on what happens if you don’t choose any license at all.

Choose an open source license: Also maintained by GitHub, this static site takes more of an interview format. You can click through to see licenses that might be appropriate if you want something “simple and permissive” or if you “work in a community”. The site includes examples of software that use each category of license. It also gives some guidance on licensing creations that aren’t software (e.g., hardware or data).

Frequently Asked Questions About the GNU Licenses: The FAQ page from the GNU licenses site, maintained by the Free Software Foundation, consolidates a variety of licensing topics. Some of the most widely used licenses, like GPL-2, GPL-3, and LGPL (see CRAN analysis above), are described here. The list of questions is long and certainly isn’t framed as a general guide or explainer. Some of the questions get into the weeds. There are a lot of questions that are geared towards use-cases involving dependencies that may or may not comply with GPL terms. The page also features a full compatibility matrix for different kinds of GPL licenses. Even if you don’t come away from this FAQ knowing the specifics of what each flavor of GPL allows, you’ll get a vivid picture of copyleft intentions.

Pick a License, Any License: When you’re looking for licensing guides, this post is a top result. Published on a developer’s blog in 2007, it takes a different tone than I have. The author leans into the hurdles licenses present. But while the message reduces licenses to a “necessary evil”, the post does encourage awareness and features a table that describes a dozen licensing models in simple, punchy language.

Source-available, in contrast to open-source as defined by OSI, means that the source is available to view, inspect, and if the license allows it, to be modified, shared, and redistributed, possibly for downstream commercial use.

CRAN is updated daily. The data presented here are based on CRAN contents as of 2026-02-14.

Copyleft refers to open-source licensing practices that require derivative works to use the same or compatible license terms. Copyleft licenses can be “strong” or “weak”, depending on what they consider to be derivative work. It’s worth noting that this analysis does not distinguish between strong and weak copyleft.

Not all license types could be determined by license name. CRAN allows maintainers to include a custom license file. This is rarely used relative to the more standard license types.

As of writing, usethis has been downloaded ~31 million times.

Take uv for example: https://blog.stephenturner.us/p/uv-part-1-running-scripts-and-tools

One more recent (May 2025) post offers a “retrospective” on the Anaconda licensing changes: https://licenseware.io/retrospective-on-anacondas-2024-licensing-changes-what-they-mean-and-smarter-alternatives/

Terms of service change. The description here is based on the Anaconda Legal page accessed in February 2026: https://www.anaconda.com/legal