Expertise Before Augmentation

A developmental framework for sequencing AI use in PhD training

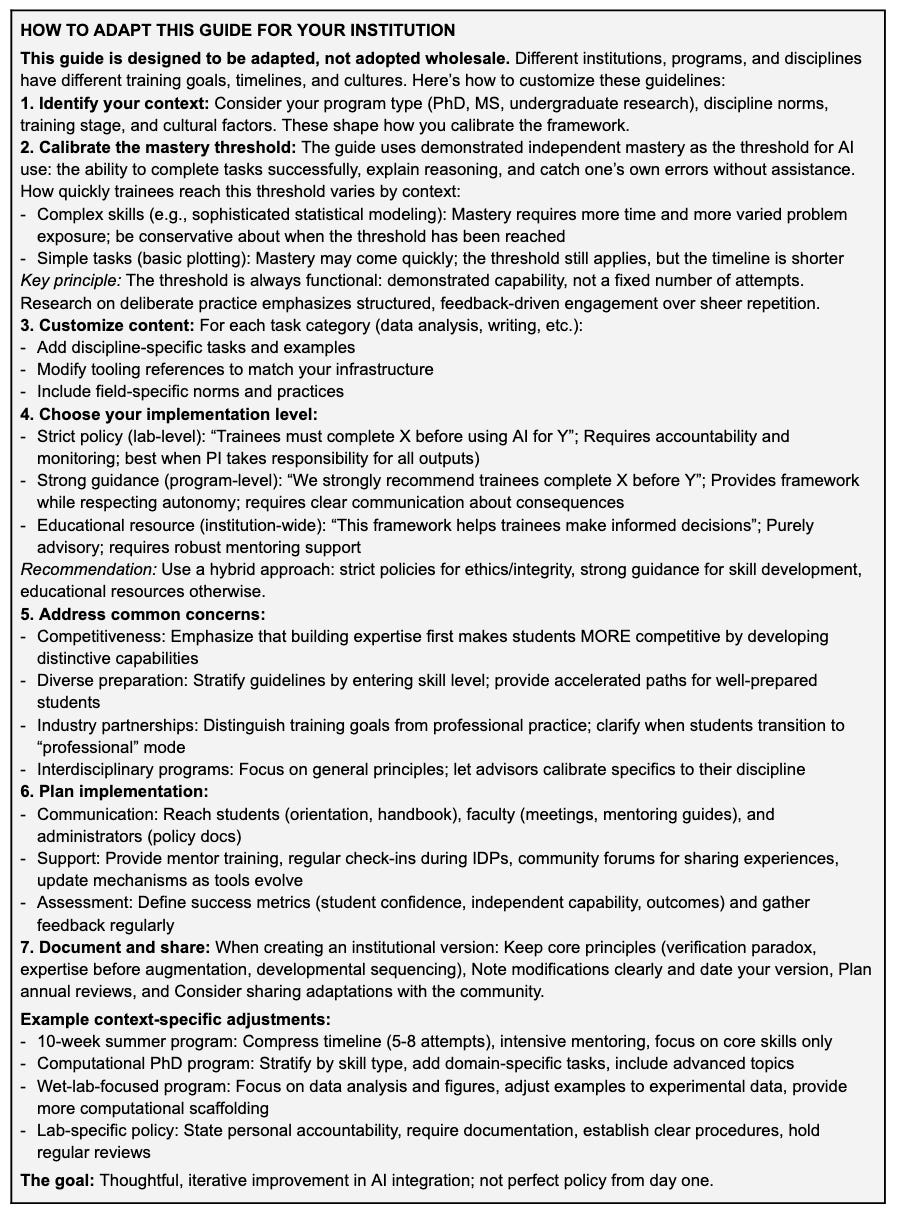

Arjun Krishnan (lab, Bluesky), is a biomedical informatics researcher and co-director of PhD training programs at the University of Colorado Anschutz, has published a pair of complementary pieces that articulate something I’ve been thinking about for a while but have struggled putting into words: generative AI is a genuinely useful tool for research and learning, but when introduced too early in training, it can undermine the very expertise it’s supposed to augment.

The first is a manuscript that establishes the core principles. The second a guide that translates those principles into actionable protocols for common PhD training activities.

1. The manuscript: build expertise first

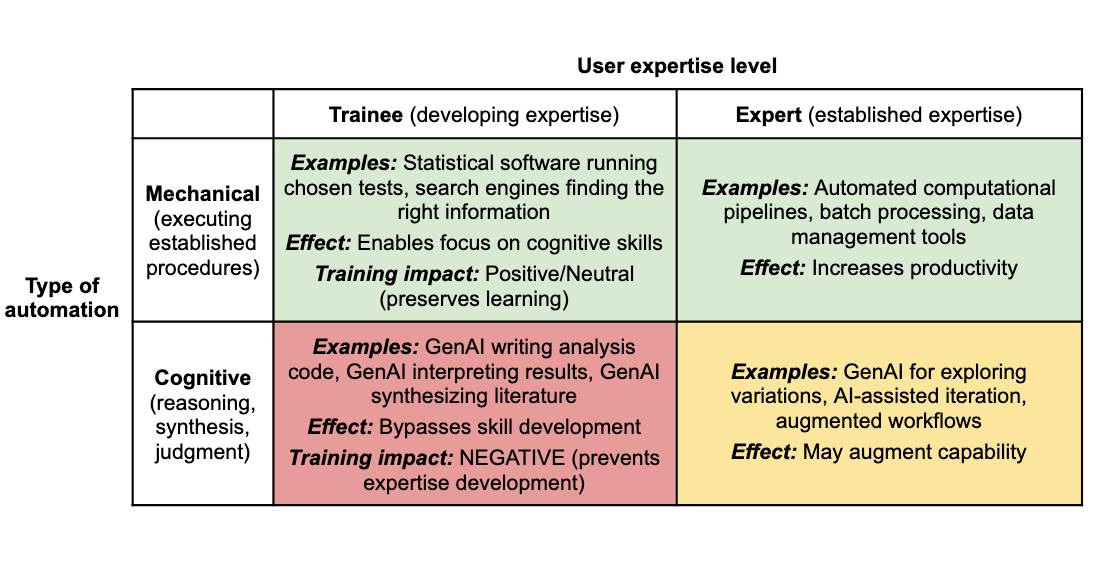

The first piece, “Build expertise first: why PhD training must sequence AI use after foundational skill development,” lays out the conceptual framework. Krishnan draws a sharp line between what he calls mechanical automation and cognitive automation. Previous technologies like calculators, statistical software, and search engines automated the execution of procedures while preserving the cognitive work. You still had to decide which statistical test to run, evaluate whether assumptions were met, and interpret whether results supported your hypothesis. Generative AI is categorically different. It can formulate the analysis plan, choose the tests, generate the code, interpret the results, and draft the write-up. A trainee can complete an entire analysis without engaging in any of the thinking the training is designed to develop.

This leads to what Krishnan calls the verification paradox: you cannot meaningfully verify AI outputs if you haven’t yet developed the domain expertise that verification requires. You can’t spot errors you haven’t learned to recognize, and you don’t know what “correct” looks like without prior experience doing the work yourself. The result is a circular trap where using AI before you can verify it trains you to produce unverified work, all while the polished appearance of AI outputs creates a dangerous illusion of competence.

The solution Krishnan proposes isn’t to ban AI from training environments. The solution is sequencing. Trainees should build foundational expertise through deliberate, feedback-driven practice before using AI to augment it. The threshold is functional, not arbitrary: can you complete the task independently, explain your reasoning, and catch your own errors? Once that bar is crossed, AI use becomes not just acceptable but genuinely productive, because you now have the expertise to guide the tool, recognize when it’s wrong, and work independently when it fails.

2. A guide: expertise before augmentation

The second piece, “Expertise before augmentation: a practical guide to using generative AI during research training,” translates this framework into concrete protocols. It walks through specific research tasks (writing code, analyzing data, drafting manuscripts, reading literature, making figures) and distinguishes between uses that support learning and uses that bypass it. AI as a Socratic interlocutor that probes your understanding after you’ve wrestled with a problem? Productive. AI as an oracle that delivers a complete analysis you can’t evaluate? Counterproductive: this is dependency, not augmentation.

Arjun’s framing in this guide is useful because it moves past the stale (and IMHO, boring) debate between AI enthusiasm and AI skepticism. The question isn’t whether trainees should use AI. They will, and they should. That ship has sailed. The question is when, and the answer depends on where they are in their expertise development. The same tool that makes an experienced researcher more productive can prevent a trainee from becoming one. Getting the sequencing right is one of the more consequential pedagogical challenges facing graduate education right now, and Krishnan’s framework gives programs a principled basis for navigating it.