Tacit Knowledge and Biosecurity

What's "tacit knowledge" in biosecurity, and is it really a barrier? A look at the 2025 RAND paper "Contemporary Foundation AI Models Increase Biological Weapons Risk." 1.8k words, 8 min reading time.

Lately I’ve been thinking (and writing) a lot about biosecurity, and its intersection with AI and biotechnology (AIxBio). I.e., how AI might increase the risk that a non-state actor is able to successfully create a biological weapon. I’ve included some primers on this topic at the end of this post to get up to speed on the topic.

The real story is not just what AI can do in a computational benchmark. It’s what a person can actually do in building and troubleshooting protocols and carrying those out at the bench, under real-world constraints, with all the little decisions and troubleshooting steps that never make it into a methods section. In other words, there’s an interesting question about whether a limiting factor is tacit knowledge, and whether AI meaningfully lowers that barrier, or just makes the explicit parts of the workflow look deceptively easy.

The RAND paper on AI and bioweapons risk

RAND published a revised/final version of a new paper late last year:

Brent, R., & McKelvey, G. (2025). Contemporary Foundation AI Models Increase Biological Weapons Risk. https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA3853-1.html

The Center on AI, Security, and Technology (CAST) at the Global and Emerging Risks division at the RAND corporation aims to examine opportunities and risks of rapid technological change focusing on AI, security, and biotech. In this paper, Roger Brent and Greg McKelvey consider whether already-deployed foundation models might increase biological weapons risk by successfully guiding users through the technical processes required to develop biological weapons.

There’s a lot that’s interesting in this paper, and I’m not actually going to go into the methods and results here. I really enjoyed reading the section really digging into what “tacit knowledge” really means. After all, their central claim is that we should retire the presumption that tacit knowledge is required to produce biological weapons, and argue for new benchmarks that evaluate models’ abilities to guide users through key steps in producing such weapons.

What is “tacit knowledge” in biology?

The paper takes time to really introduce what we mean by “tacit knowledge,” referencing papers going back to the 1940s.

The idea of tacit knowledge has two key 20th-century lineages. In economics, Friedrich von Hayek used it to explain how buyers and sellers act on local, situation-specific understanding that often can’t be fully put into words (von Hayek, 1945). The combined effect of those private judgments shows up in market prices, which effectively encode information that no single person can completely articulate.

In the natural sciences, tacit knowledge is most closely tied to Michael Polanyi, who argued that scientific advances rely not only on explicit methods but also on know-how carried through traditions, learned practices, and implicit standards, including values and background assumptions (Polanyi, 1966).

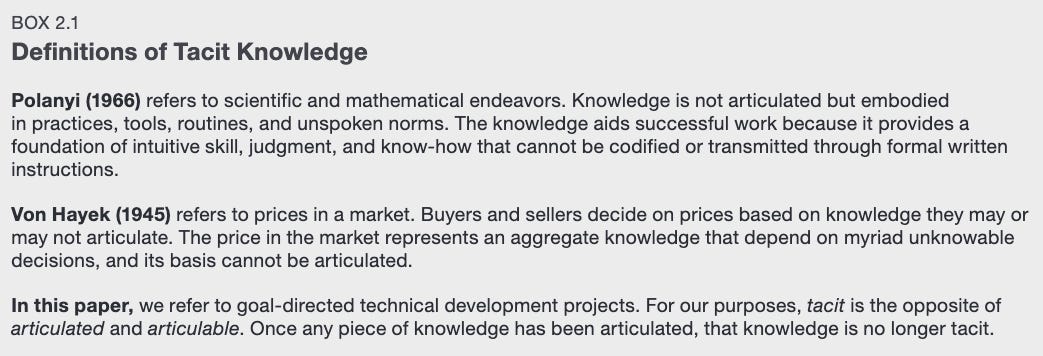

For the purposes of discussion around AIxBio and biosecurity, the RAND whitepaper itself lays out three definitions of tacit knowledge in Box 2.1.

That is, knowledge relevant to a goal-directed technical development project that can’t be easily articulated. In other words, once you can express tacit knowledge in words, it’s no longer tacit.

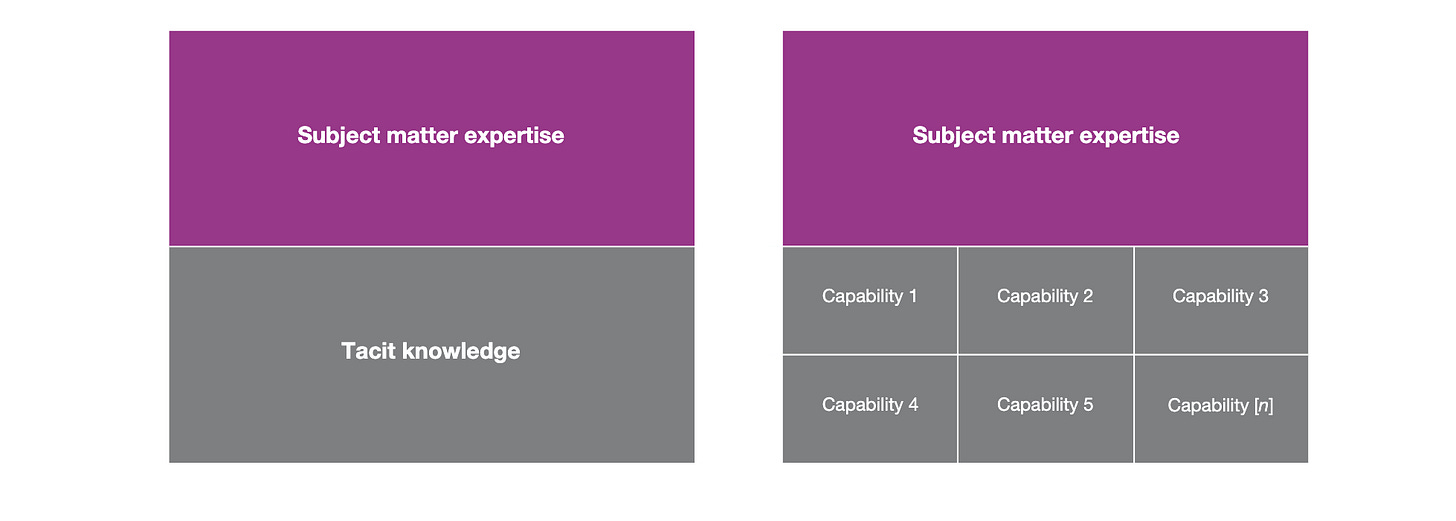

The paper makes an argument that the “tacit knowledge barrier” really isn’t a barrier at all, because tacit knowledge can be broken down into different capabilities, each of which can be explicit, and which AI models might actually be able to articulate guidance.

Case study: Anders Breivik

The paper opens with an interesting case study on Norwegian ultranationalist Anders Breivik, who successfully developed the technical expertise to carry out tricky chemical syntheses and built a bomb using opensource information found via the internet.

The account presents a case in which a lone actor carried out a multi-stage, technically demanding development process that spanned the full arc from initial idea through deployment. He succeeded not only in planning and design, but also in obtaining necessary inputs, producing key components, and integrating them into a functioning device, despite lacking formal scientific training. The narrative emphasizes that he relied heavily on online sources to learn and adapt, and that he documented his work in a way that blended record keeping with guidance for others. Crucially, his notes highlight that success depended on more than following written instructions: he had to navigate practical constraints, make context-dependent choices among alternatives, and repeatedly troubleshoot unexpected problems. The example is used to illustrate how accessible information, persistence, and iterative problem-solving can substitute for formal expertise in accomplishing complex technical tasks, especially when the individual is motivated to learn and adjust in response to failure.

Brevik had no real scientific training but was able to acquire the necessary knowledge to achieve his goal using the internet. And he demonstrated this in his manifesto (NSFW), which is a bit of a combination of a lab notebook and an instruction manual to teach his future Neo-Nazi colleagues to make bombs.

The authors of this paper spent an entire chapter discussing the details of Breivik’s efforts to illustrate the level of technical proficiency he acquired without real training or apprenticeship.

The authors assert that the complexity of the operations described by Breivik easily exceeds the complexity of the molecular biological and cell culture manipulations used in work with animal viruses.

They use this as a jumping off point to identify elements of technical success to inform new AI safety benchmarks.

Conclusions from the RAND paper

The authors’ bottom line is that we should reconsider taking comfort in the idea that “tacit knowledge” meaning hard-to-verbalize lab know-how is a reliable barrier to bioweapons development, because modern foundation models can supply a lot of the “in-words” guidance that matters for getting complex technical work done. They argue that many existing AI lab safety assessments underestimate risk because they lean on that tacit-knowledge premise and on benchmarks that do not faithfully represent what real-world success looks like for a motivated actor. They then claim, based on their own framework and model interactions, that late-2024 frontier systems can provide meaningful assistance, and that risk grows further because the guidance can generalize beyond a single example, models can be induced via plausible dual-use cover stories, and the net effect is to expand the pool of people who could execute complicated biological tasks.

They endorse building more comprehensive, task-grounded benchmarks that explicitly test the “elements of success” in biological weapons development. They emphasize urgency around mitigation and stronger safeguards, including access controls and other interventions that constrain who can use the most powerful models and who can obtain sensitive enabling capabilities.

References

Here are a few recent academic publications and whitepapers from the likes of RAND, NASEM, CNAS, and others to use as a primer on the topic of AIxBio and biosecurity. I created a slightly more comprehensive list here.

Aveggio, C., Patel, A. J., Nevo, S., & Webster, K. (2025). Exploring the Offense-Defense Balance of Biology: Identifying and Describing High-Level Asymmetries. RAND. https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA4102-1.html

Brent, R., & McKelvey, G. (2025). Contemporary Foundation AI Models Increase Biological Weapons Risk. https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PEA3853-1.html

Committee on Assessing and Navigating Biosecurity Concerns and Benefits of Artificial Intelligence Use in the Life Sciences, Board on Life Sciences, Division on Earth and Life Studies, Computer Science and Telecommunications Board, Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences, Committee on International Security and Arms Control, Policy and Global Affairs, & National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2025). The Age of AI in the Life Sciences: Benefits and Biosecurity Considerations (p. 28868). National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/28868

Del Castello, B., & Willis, H. H. (2025). Assessing the Impacts of Technology Maturity and Diffusion on Malicious Biological Agent Development Capabilities: Demonstrating a Transparent, Repeatable Assessment Method. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA3662-1.html

Dettman, J., Lathrop, E., Attal‐Juncqua, A., Nicotra, M., & Berke, A. (2026). Prioritizing Feasible and Impactful Actions to Enable Secure AI Development and Use in Biology. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, bit.70132. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.70132

Dev, S., Teague, C., Brady, K., Lee, Y.-C. J., Gebauer, S. L., Bradley, H. A., Ellison, G., Persaud, B., Despanie, J., Del Castello, B., Worland, A., Miller, M., Maciorowski, D., Salas, A., Nguyen, D., Liu, J., Johnson, J., Sloan, A., Stonehouse, W., … Guest, E. (2025). Toward Comprehensive Benchmarking of the Biological Knowledge of Frontier Large Language Models. https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WRA3797-1.html

Drexel, B., & Withers, C. (2025). AI and the Evolution of Biological National Security Risks. Center for New American Security. https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/ai-and-the-evolution-of-biological-national-security-risks

Endy, D. (n.d.). Biosecurity Really: A Strategy for Victory.

Ho, A. (2025, June 13). Do the biorisk evaluations of AI labs actually measure the risk of developing bioweapons? Epoch AI. https://epoch.ai/gradient-updates/do-the-biorisk-evaluations-of-ai-labs-actually-measure-the-risk-of-developing-bioweapons

Laurent, J. M., Janizek, J. D., Ruzo, M., Hinks, M. M., Hammerling, M. J., Narayanan, S., Ponnapati, M., White, A. D., & Rodriques, S. G. (2024). LAB-Bench: Measuring Capabilities of Language Models for Biology Research (No. arXiv:2407.10362). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.10362

Li, N., Pan, A., Gopal, A., Yue, S., Berrios, D., Gatti, A., Li, J. D., Dombrowski, A.-K., Goel, S., Phan, L., Mukobi, G., Helm-Burger, N., Lababidi, R., Justen, L., Liu, A. B., Chen, M., Barrass, I., Zhang, O., Zhu, X., … Hendrycks, D. (2024). The WMDP Benchmark: Measuring and Reducing Malicious Use With Unlearning (No. arXiv:2403.03218). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.03218

Pannu, J., Bloomfield, D., MacKnight, R., Hanke, M. S., Zhu, A., Gomes, G., Cicero, A., & Inglesby, T. V. (2025). Dual-use capabilities of concern of biological AI models. PLOS Computational Biology, 21(5), e1012975. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1012975

Pannu, J., Gebauer, S. L., Bradley, H. A., Woods, D., Bloomfield, D., Berke, A., McKelvey, G., Cicero, A., & Inglesby, T. (2025). Defining Hazardous Capabilities of Biological AI Models: Expert Convening to Inform Future Risk Assessment. https://www.rand.org/pubs/conf_proceedings/CFA3649-1.html

Titus, A. (2023). Violet Teaming AI in the Life Sciences A Preprint. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8180396

Webster, T., Moulange, R., Del Castello, B., Walker, J., Zakaria, S., & Nelson, C. (2025). Global Risk Index for AI-enabled Biological Tools. The Centre for Long-Term Resilence & RAND Europe. https://doi.org/10.71172/wjyw-6dyc