Scientific production in the era of large language models

With the production process rapidly evolving, science policy must consider how institutions could evolve

An interesting policy article was published in Science last month.

Keigo Kusumegi et al. Scientific production in the era of large language models. Science 390, 1240-1243 (2025). DOI:10.1126/science.adw3000.

The study set out to understand the macro-level impact of LLMs on the scientific enterprise. It’s a short paper, and it’s worth reading in full.

A clever approach to identifying LLM assistance

AI detectors are notoriously unreliable. But that’s because most of the time you hear about these they’re used for making individual assessments: Did this student write the essay with Chat? Was this manuscript written by Claude? Here the authors took an interesting approach, and suspected LLM-assistance usage was used for making statistical inferences on a population, not individual papers.

Here’s the gist. They collected millions of preprints from arXiv, bioRxiv, and SSRN from 2018-2024. They examined the word distribution of papers submitted prior to 2023 (pre-ChatGPT) to estimate the word distribution of human-written text.

Then they asked ChatGPT to rewrite the abstracts of all these papers, and did the same analysis to get the word distribution for LLM-assisted writing. It’s not perfect, but quantifying the difference in word distribution between known-human written text and known LLM-written text can help identify probable LLM-assisted abstracts written after the release of ChatGPT. Again, it’s problematic if individual decisions were being made on this or that paper, but as a tool to probabilistically bin papers into LLM-assistance-yes and LLM-assistance-no for downstream statistical analysis isn’t as problematic because some error is expected and tolerated in any kind of statistical inference application.

They identified an author’s initial adoption of LLMs by marking the first manuscript that exhibited statistical signatures of LLM assistance above some detection threshold. Here are the two main findings.

1. Productivity goes up after adopting LLMs

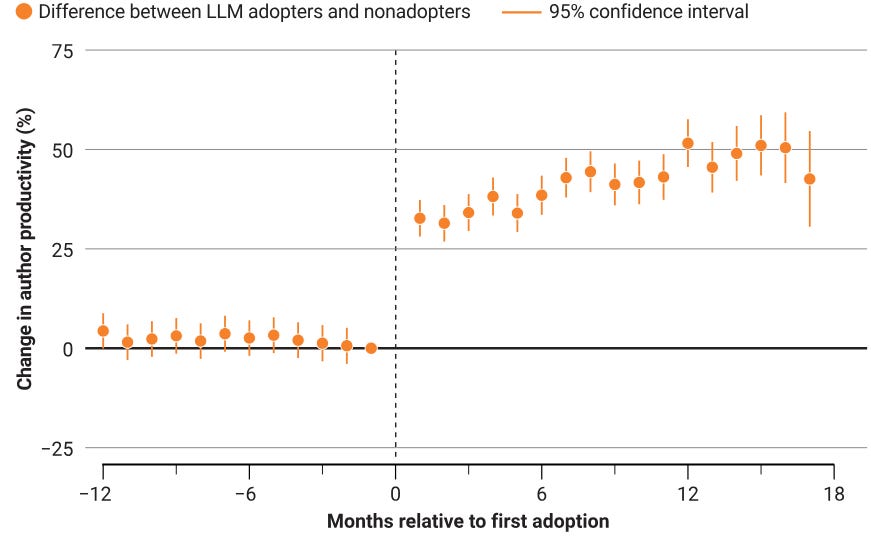

Between January 2022 and July 2024, the number of preprints published once an author had adopted LLMs in their writing increased by 36.2% relative to nonadopters.

That one’s no surprise. Here’s the really interesting one.

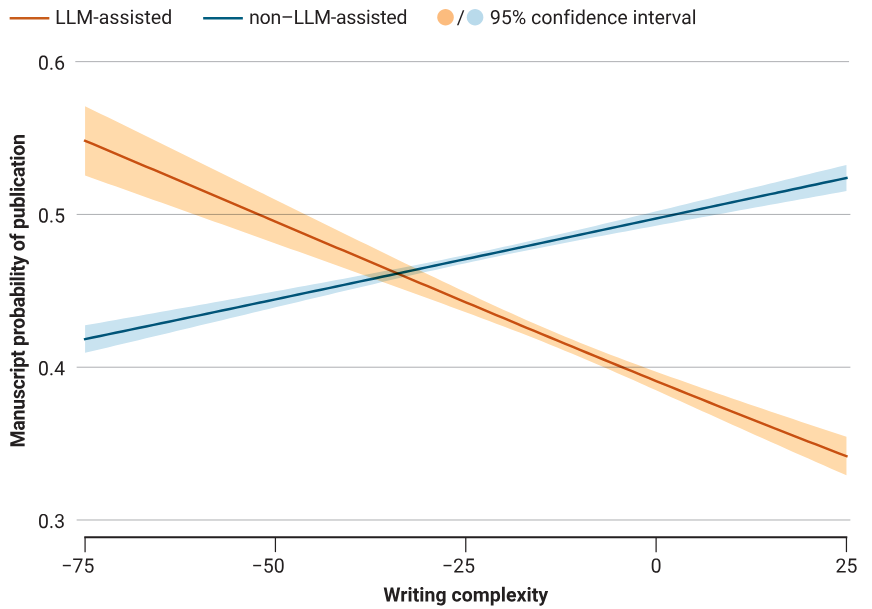

2. Writing complexity for LLM-assisted manuscripts is correlated with a lower probability of being published, but the relationship is inverted for human-written text.

This is where it gets super interesting. They then looked at writing complexity using the Flesch reading ease score, which is a composite of average sentence length and syllables per word. They created a proxy measure of quality by creating a binary outcome defined as future publication in a peer-reviewed journal or conference.

When they correlated complexity with publication outcomes a few patterns became clear.

First, complexity was higher for LLM-assisted papers than for human written papers. I.e., LLMs can produce complex-sounding scientific writing.

Second, for non-LLM-assisted writing, writing complexity was associated with higher manuscript quality (based on the proxy measure of publication probability).

Third, and most interesting, for LLM-assisted writing, the relationship flipped — writing complexity was associated with lower peer assessment of scientific merit.

What it all means

This short paper really shows that LLMs are reshaping how scientific literature is being written, and the results show a serious issue that we’re all facing.

As a shortcut to (imperfectly) screen scientific research, writing characteristics are fast becoming uninformative signals, just as the quantity of scientific communication surges. As traditional heuristics break down, editors and reviewers may increasingly rely on status markers such as author pedigree and institutional affiliation as signals of quality, ironically counteracting the democratizing effects of LLMs on scientific production.

The authors cram a lot of other really interesting tidbits into a 4 page paper, including deeper analysis into native English speakers vs non-native writers, individual analyses across the three different repositories (arXiv, bioRxiv, SSRN), and an interesting analysis of how LLM-assisted writing results in different literature citation practices. The paper also acknowledges limitations of the study. And the 72-page supplement has lots of interesting data points as well.

Keigo Kusumegi et al. Scientific production in the era of large language models. Science 390, 1240-1243 (2025). DOI:10.1126/science.adw3000.