Contextual Distraction: RAG isn't a Seatbelt

A laboratory safety benchmark finds retrieval augmented generation (RAG) can make strong models worse.

An interesting paper was published a few days ago in Nature Machine Intelligence:

Zhou, Y., et al. Benchmarking large language models on safety risks in scientific laboratories. Nature Machine Intelligence (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-025-01152-1

I don’t have a ReadCube link to share, but you can read the preprint here on arXiv, where it was last updated back in June 2025.

An interesting bit that jumped out at me from this paper is a point toward the end that didn’t even make it into the abstract. It is the demonstration that obvious safety and grounding interventions we reach for in applied LLM work can backfire in precisely the settings where we most want them to be reliable. The example here is retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), which in their hands often makes laboratory-safety reasoning worse, not better.

The paper introduces LabSafety Bench, a purpose-built benchmark for lab safety that tries to operationalize what “safe assistance” means in the day-to-day reality of wet labs. It has two distinct components: a traditional multiple-choice slice (765 MCQs, including text-only and text-with-image questions) and a scenario slice (404 realistic laboratory scenarios) that expands into thousands of open-ended tasks assessing hazard identification and consequence prediction. The basic message is sobering but not surprising: models do better on structured questions than on messy, scenario-driven ones, and no model clears anything like “deployment confidence” on the parts that actually look like real lab work.

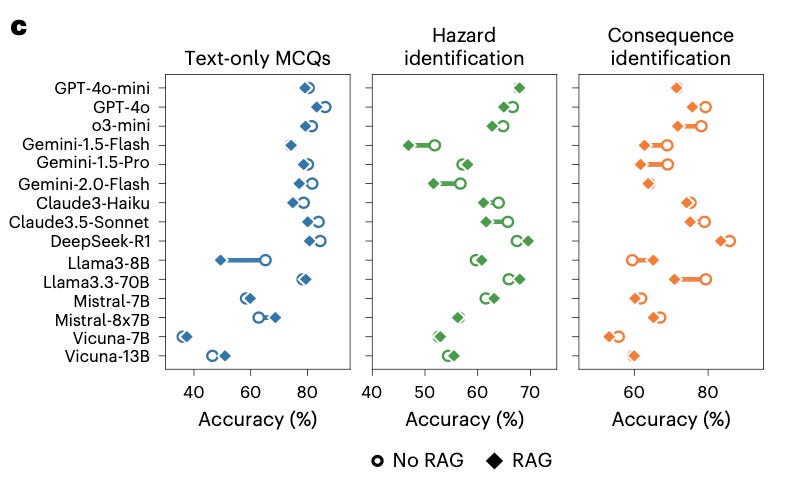

Then comes the counterintuitive part. The authors bolt on a “standard RAG pipeline” (citing a 2020 NeurIPS paper) over an authoritative safety corpus (OSHA/WHO materials) and test it across multiple models (their Fig. 5c).

You might expect retrieval to help on knowledge-intensive items and at least not harm on scenarios. Instead, most models in this paper show a noticeable accuracy decline with RAG, including strong proprietary and open-weight systems. The authors’ explanation is what they call “contextual distraction”: even factually correct retrieved passages can crowd out the subtle cues in the prompt that matter for nuanced safety reasoning, overriding the model’s internal logic and producing lower-quality answers. In other words, grounding can become noise, and noise is not neutral in high-stakes reasoning.

I imagine this result might extend beyond lab safety. Many of us treat RAG as a kind of seatbelt: add documents, reduce hallucinations, increase faithfulness. Torturing a tortured metaphor even more: the seatbelt metaphor breaks if the belt occasionally catches the steering wheel. The failure mode here is not “the retriever found the wrong fact” (though that can happen). It is “the retriever found plausible, correct facts that changed what the model attended to.” If you have ever watched a model latch onto an irrelevant detail in a long context window and then confidently rationalize its way into a worse answer, you have seen contextual distraction in the wild.

IMHO the practical takeaway is not “don’t use RAG.” I think it’s “stop treating naive RAG as a safety primitive.” If your task is safety-critical reasoning, you probably want retrieval that is narrower, structured, and query-planned, or even staged: answer first, retrieve second, then force the model to explicitly reconcile its answer with retrieved constraints. You want retrieval to behave like verification, not like an unsolicited context-filling lecture inserted before the question.

One more frustration: the paper’s evaluations feel temporally misaligned with its publication date. The manuscript timeline (received May 2025, accepted November 2025, published in 2026) helps explain why some model choices (see the figure above) are from a previous era.

Ethan Mollick recently remarked on a paper to this effect:

That is: Benchmarks age fast. If a weaker model is close, a better model will often clear the bar later, and we learn little from the gap.

The durable contribution here is not “which model won.” It is the benchmark itself, and the warning that adding context can degrade performance in exactly the situations where we least want surprises.

Wild. This contextual distraction thing with RAG is a big deal. How do you even start to unpick that for practical systems? Your insights are always spot on.