The AI Attribution Error

If an AI produces something useful it's because of your own skill in model choice, prompting, and steering. If not, it's because the model is a useless lying machine that can't follow directions.

Cite this post: Turner, S.D. (2025, December 28). The AI Attribution Error. Paired Ends. https://doi.org/10.59350/c3gt8-9h659

The fundamental attribution error

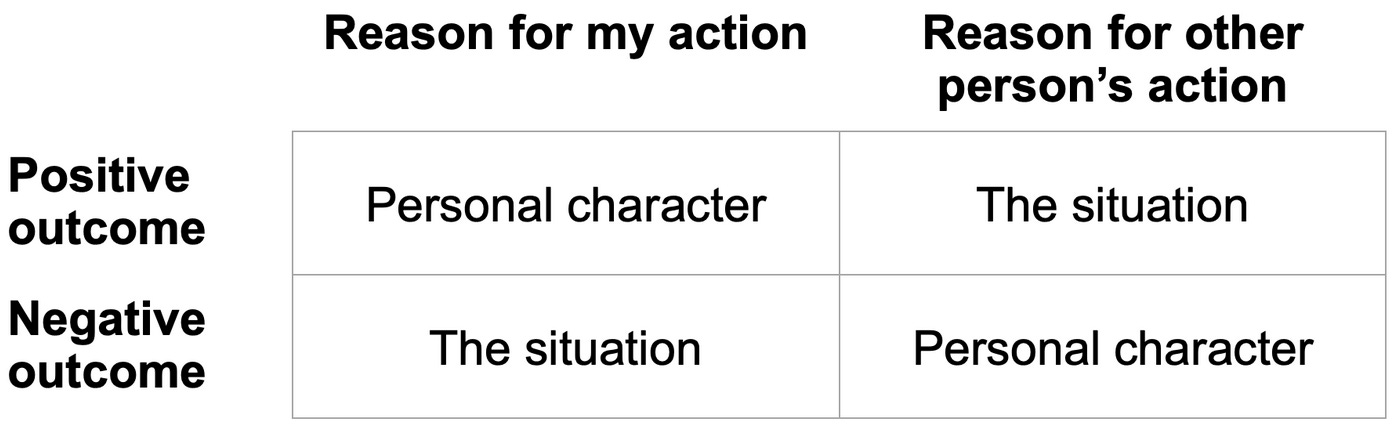

Earlier this year I learned of the fundamental attribution error. This is our tendency to blame others’ bad actions or poor decisions on their character, while we excuse our own by pointing to circumstance. I cut that guy off in traffic because I’m late for work. He cut me off because he’s a moron.

Or the inverse — we attribute our own positive outcomes to our own character, and others’ positive outcomes to situation. I arrived on time to work because I take my job seriously. He arrived on time because it’s his job.

The parental attribution error (Chris Williamson)

By extension, I recently learned of the parental attribution error. This is when we attribute our own problems to our upbringing while claiming that our strengths are ours alone. As recently described by Chris Williamson on Modern Wisdom:

You blame your parents for pushing you too hard in school, convinced that it made you perfectionistic and neurotic, but when was the last time that you acknowledged that same pressure gave you ambition and discipline and drive? You point to a childhood where mistakes weren’t tolerated as the reason that you fear failure, but what about your meticulousness, your standards, your refusal to phone it in? You complained that no one ever asked you what you wanted growing up, but could that also be why you’re so tuned in to what everyone else needs? You say your low self-worth comes from never being praised, but isn’t that the same fuel that makes you outwork everyone around you? You trace your conflict avoidance back to all of the shouting at home, but isn’t that also where your talent for de-escalation and emotional radar came from? You chalk up your hyper-independence to not being able to trust anyone, but isn’t that also what made you capable, adaptable, and calm under pressure? You say you’re emotionally guarded because no one took your feelings seriously, but isn’t that also why you’re steady when the people around you fall apart? You’ve labeled yourself a people-pleaser because you had to keep the peace at home, but maybe that’s also where your social fluency and emotional intelligence were born. You blame your poor boundaries on parents who didn’t respect yours, but isn’t that also why you’re so careful not to cross anyone else’s? You say your fear of being a burden comes from being treated like one, but isn’t that the same fear that now makes you reliable, disciplined and impossible to disappoint. You attribute your sensitivity to criticism to all of the judgment that you grew up with, but that is also what makes you thoughtful, receptive, and serious about getting better. You say your nervous system never relaxes because your home was unpredictable, but isn’t that also why you’re perceptive, quick thinking and never caught off guard? […] Your sharp edges didn’t appear out of nowhere. They’re often the byproduct of something useful.

The corporate attribution error (Cat Hicks)

This week I came across an essay from back in 2024 by Cat Hicks on the Corporate Attribution Error — confidently crediting big, real-world outcomes to a company’s intentional initiatives while underweighting (or ignoring) broader environmental and situational causes and the thinness of the evidence.

Corporate Attribution Error is what happens when a business (or anyone channeling the voice of The Business Narrative–so this could be a leader, a consultant, a spokesperson, a manager, an IC, your own mind talking to you inside of your own skull, it doesn’t really matter who it is, this describes an argument not a person, and I do not like the We Are So Smart And They Are So Stupid Exceptionalism that dominates many conversations about humanity in the workplace, so I won’t indulge it here) illogically and systematically attributes a large observed outcome in the world to the intentional and planned initiative of a business.

The AI attribution error

By extension, I’m making up a new term: the AI attribution error. It is the habit of telling a self-serving causal story about AI results, where wins get attributed to our own competence (I chose the right model, I crafted the perfect prompt, I contributed with the right “steering”) and losses get attributed to the tool’s incompetence (this AI is garbage), rather than to the joint system that produced the outcome.

In practice, it turns every interaction into a little attribution game. If the output lands, we treat it like proof of skill: I know how to use these tools. If it misses, we treat it like proof of defect: the model hallucinates, it cannot follow directions, it is a useless lying machine. But most outputs, good or bad, are not clean evidence for either story. They are a multivariate product of what we asked for, what we left out, how ambiguous the task was, whether we provided the right constraints and examples, whether we verified anything, and what the model can reasonably infer from limited context.

What makes it an error is not that models are reliable, or that prompting is irrelevant. It is that the narrative collapses a messy process into a flattering explanation on the way up and a scapegoat on the way down. If you want to think about it more honestly, the question is rarely “is this model good or bad?” and more often “did I set up the conditions where success was likely, and did I test the result in a way that would catch failure?”