AI Amplifies Careers and Compresses Fields

A new study in Nature finds that AI adoption correlates with faster career ascent and higher citation impact, while the semantic spread of entire fields subtly contracts around fewer topical regions.

An interesting new paper was published last week in Nature by researchers at Tsinghua University, Zhongguancun Academy, University of Chicago, and the Santa Fe Institute.

Hao, Q., Xu, F., Li, Y. et al. Artificial intelligence tools expand scientists’ impact but contract science’s focus. Nature (2026) 10.1038/s41586-025-09922-y. Read free: https://rdcu.be/eZgSz.

The paper was covered in a Science commentary: AI has supercharged scientists—but may have shrunk science.

The provocative claim this paper isn’t that AI makes individual scientists more productive. It is that the same forces that help a person “win” can make a field collectively smaller.

One line in the paper captures the tension cleanly: “an emerging conflict between individual and collective incentives” in AI adoption. In their data, AI use is associated with “expanded personal reach and impact,” while the field’s “knowledge extent” shrinks.

These results generally highlight an emerging conflict between individual and collective incentives to adopt AI in science, where scientists receive expanded personal reach and impact, but the knowledge extent of entire scientific fields tends to shrink and focus attention on a subset of topical areas.

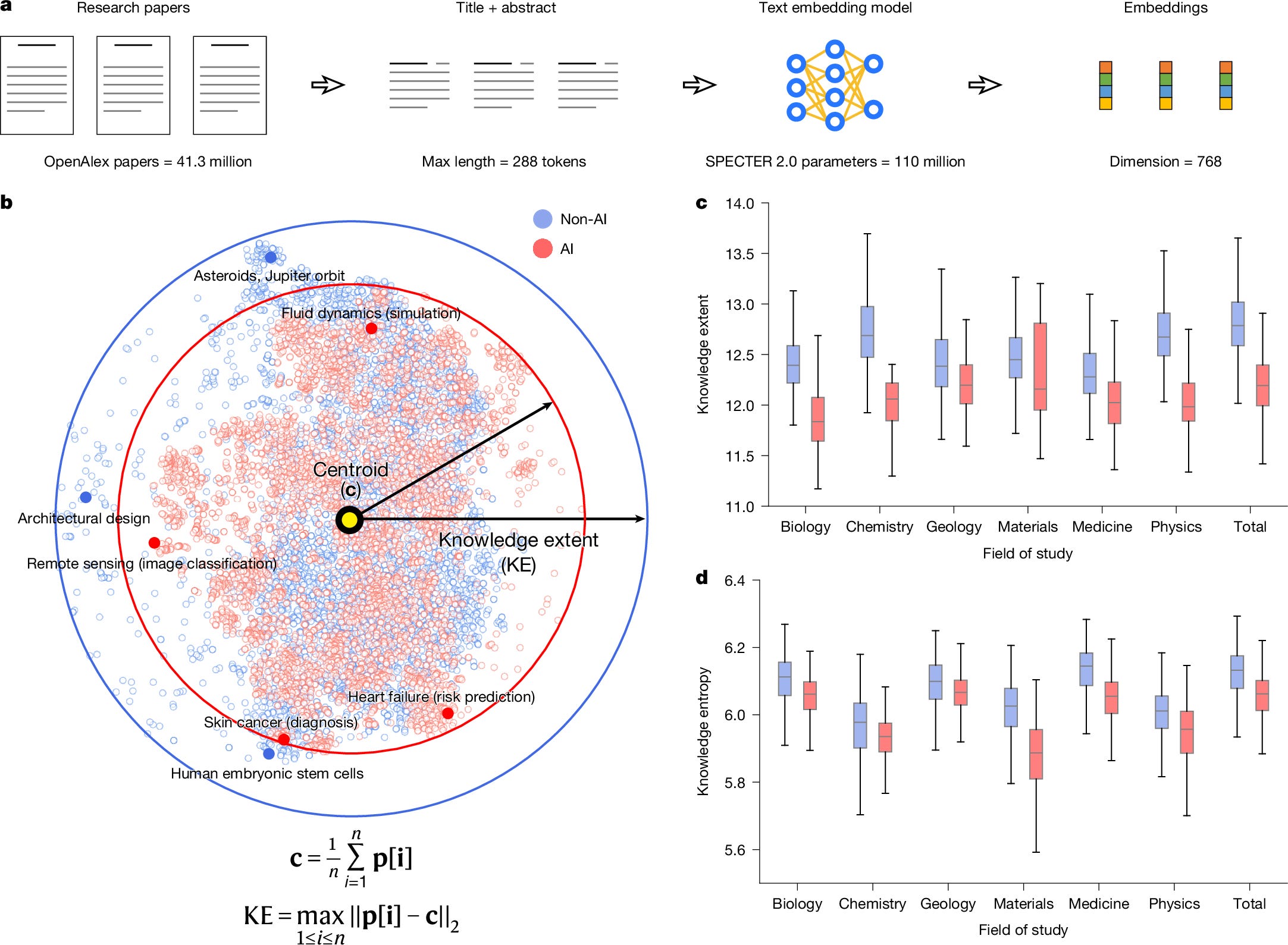

The individual upside is large. Across 41.3 million natural-science papers (1980–2025), the authors classify about 311k as AI-augmented using a fine-tuned language model on titles and abstracts, validated against expert labels. They report that AI-adopting scientists publish about 3.0x more papers, receive about 4.8x more citations, and reach “project leader” status sooner. Even if you immediately raise the obvious questions about selection effects and what counts as “using AI,” the directionality is hard to ignore: adoption correlates with career acceleration.

But Figure 3 is where the paper becomes a science policy argument. The authors embed papers into a 768-dimensional semantic space (SPECTER 2.0) and define “knowledge extent” as the diameter of a sampled cloud of papers (max distance from the centroid). In the t-SNE visualization, AI papers cluster more tightly; in the field-by-field boxplots, AI samples show lower knowledge extent and lower entropy of topic distribution. The headline number is modest but consistent: a roughly 4.6% contraction in median knowledge extent, seen across all six disciplines.

Optimization tends to pull effort toward whatever is easiest to measure, easiest to benchmark, and easiest to publish. A diameter-based metric also makes the periphery matter: if fewer papers explore the weird edges of a field, the cloud’s “reach” shrinks even if the center stays busy. The paper’s interpretation is that data availability is the gravity well. AI works best where data are abundant, so attention drifts toward already-instrumented problems, not necessarily the most important or conceptually fertile ones.

By contrast, data availability seems to be a major impacting factor, where areas with an abundance of data are increasingly and disproportionately amenable to AI research, contributing to the observed concentration within knowledge space.

Science’s coverage frames this as an incentives problem, with memorable quotes about “alarm bells,” “pack animals,” and a feedback loop where popular problems generate datasets that, in turn, attract more AI work. It also points to a pragmatic intervention: build better datasets in domains that are currently data-poor, so AI’s benefits are not confined to the same crowded mountains.

The source code for the paper is here on GitHub: https://github.com/tsinghua-fib-lab/AI-Impacts-Science. The dataset of AI in natural science research across 41.3 million papers is available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15779090.